(EN) (TR) (ES)

What we call writing is not such an old invention. If we had the means to gather all the diverse content we’ve written so far—novels, stories, poems, sacred books, blog posts—into a pool and examine what we’ve talked about, how we’ve talked about it, and how often, what would we find? Have we spent all these years cooking and serving just 3-5 topics? Is there a modelable plot structure underlying the literary works we call cult? In other words, if we discover this model, could we somehow produce a ‘successful’ work too? Or, as claimed by Russian Formalist literary theorists (like Roman Jakobson, Osip Brik, Yuri Tinyanov) who emerged before the 1917 Russian Bolshevik Revolution, is literature not a mystical mode of production but rather a phenomenon with its own unique laws, structures, and models? Could someone else have written something with a similar impact based on a similar model, even if Shakespeare hadn’t written Romeo and Juliet?

The topic is vast. Providing convincing answers to the above questions is no easy task. However, there are certainly various attempts. Recent work in areas like ‘Big Data’ and ‘Data Processing’, which are trendy concepts nowadays, deals with these questions. Not only literary-focused analyses but also the discovery of underlying models for various human behaviors is quite popular, both in social sciences and marketing. With the help of programs like R or Python, there’s research on a myriad of topics, from social media shares to consumer behaviors and Google searches.

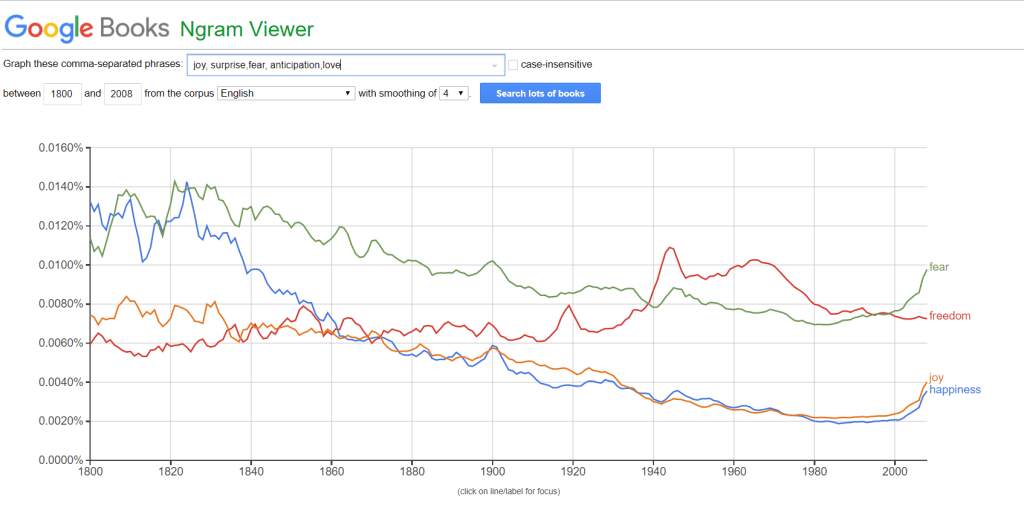

However, when it comes to books and literature, the first thing that comes to mind is the Ngram application, which allows us to analyze printed books digitized through Google over the past few centuries. With Ngram, it is possible to observe how the usage of certain words in books has changed over time. For instance, I selected a couple of arbitrary words and their distribution in books digitized by Google between 1800 and 2018.

Let’s take the word “freedom” as an example. After both World Wars, there is a spike in the usage of this word (naturally). Unfortunately, after the 1980s, the word ‘freedom’ loses its place in the literary agenda. Looking at the flow after the 2000s, we see an increase in the usage of words like fear, entertainment, and happiness, while the word ‘freedom’ seems to be playing dead in this movement. Of course, this simple observation doesn’t hold much significance; it’s merely a small intellectual toy at this stage.

However, the article below discusses how various researchers examine the content of significant literary products (or thousands of books through online and free platforms like the Gutenberg Project). Rather than merely analyzing the raw frequency of a word’s usage within works like in Ngram, here a more interesting method is employed. The position of words on a single emotional scale is determined (words that evoke positive feelings receive a (+), and negative ones a (-) score). Subsequently, due to the change in the frequency of words used within the flow of the book, a model emerges centered on the time-average emotional score of the book.

Whether such modeling is done scientifically or not aside, it is a well-known fact that authors and directors in the film and book industry are pressured to produce products in line with ‘successful’ content and narrative flows and that the industry is funded to follow these patterns. Without prolonging the discussion, let’s turn to Miriam Quick:

Every written story has one of these 6 plot structures.

Kurt Vonnegut defines his master’s thesis on anthropology as ‘my finest contribution to culture’, and continues, ‘it was rejected because it was very simple and fun’. Although the thesis vanished without a trace, Vonnegut continued to emphasize its fundamental claim throughout his life. The claim was: ‘Stories have certain structures that can be depicted on graph paper’.

In a class in 1995, Vonnegut drew various story curves on the board, illustrating how the fate of the main character changes along an axis from ‘good’ to ‘bad’ throughout the story. These curves include arcs where the protagonist gets into trouble and escapes (‘people love these types of stories and never get tired of them’) or where the protagonist obtains something precious, then loses it, and finally regains it at the end of the story, like in the ‘boy gets the girl’ flow. ‘There’s no answer to why we don’t model these simple story curves on the computer,’ says Vonnegut, adding, ‘They are indeed quite beautiful curves.’

Fortunately, thanks to text mining techniques, Vonnegut’s request has been fulfilled. Professor Matthew Jockers from the University of Nebraska, followed by researchers from the University of Vermont’s ‘Computational Story Lab’, analyzed data from thousands of novels and identified six fundamental story types that constitute the structure of quite complex stories, which can also be referred to as archetypes. The Vermont researchers described these six story types behind English novels around 1700 as follows:

- From disaster to relief – A gradual rise from bad fortune to good

- From relief to disaster – A fall from good to bad, a tragedy

- Icarus – Luck smiling first, then a reverse fall

- Oedipus – A fall first, then a rise and again a fall

- Cinderella Story – Rise, fall, rise

- Hero in a Jam – Fall and rise

Researchers used sentiment analysis techniques to gather data. This technique is preferred mainly by market researchers analyzing social media shares, such that each word corresponds to a specific ‘sentiment score’ based on crowd-sourced data. Depending on the chosen lexicon, a word can correspond to a positive (happy) or negative (unhappy) sentiment, or one or more of the eight primary emotions like fear, joy, surprise, or anticipation. For example, the word ‘happy’ is positive and corresponds to feelings of joy, security, and anticipation. The phrase ‘to eliminate’ is negative and relates to the feeling of hate.

By analyzing all the words in a novel, poem, or play using sentiment analysis techniques and creating a map of the results over time, it becomes possible to extract the emotional shifts within a text, in other words, the emotional narrative of the writing. Although this method may not be perfect since it does not focus on the meanings of words or evaluate them within context, it can be surprisingly informative when applied to large-scale texts, as shown in data scientist Julia Silge’s blog post analyzing Jane Austen’s novels. Tools for conducting sentiment analysis are available for free, and moreover, many literary works can be downloaded from online repositories like the Gutenberg Project without copyright issues. We also attempted to identify these six types of story structures by examining the most loved works in BBC Culture’s survey titled ‘100 Stories That Changed the World’.

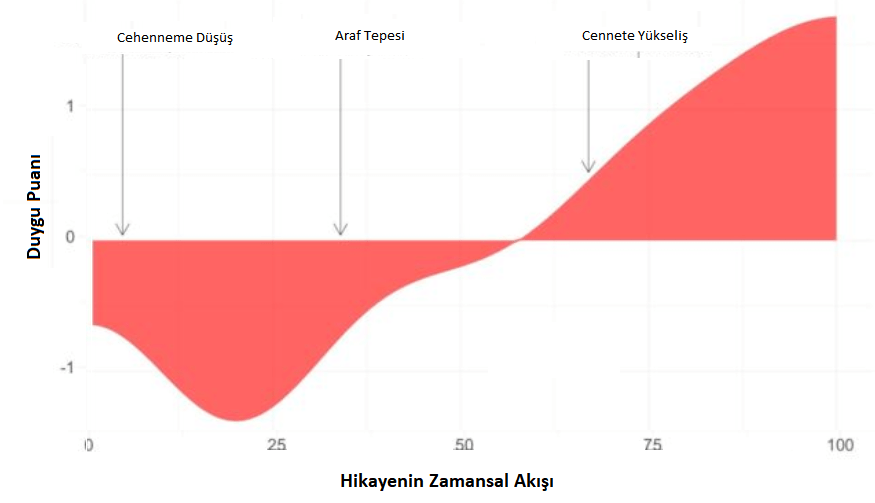

Divine Comedy (Dante Alighieri, 1308-1320) Translation: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Story Type: From Disaster to Relief

In the ‘Hell’ section of Dante’s densely structured and elegantly symmetrical poetic epic, we descend into the underworld with the poet Virgil—who else? At the beginning of the Divine Comedy, things start off badly, with a low emotional score, and as our hero descends through the circles of hell, this score drops even further (Here we can see traces of a ‘Hero in a Jam’ style arc, as this is literally correct in such a metaphorical writing). After miraculously surviving in hell, our heroes begin to climb to the Hill of Purgatory, where sinful, slothful, and excommunicated souls reside, and eventually, Dante’s ideal woman, Beatrice, takes Virgil’s place during this companionship. The poet, understanding the essence of virtue and merging with the idea of ‘love, which turns the sun and other stars,’ moves toward the exit into Paradise, filled with ever-increasing joy.

Madame Bovary (Gustave Flaubert, 1856) Translation: Eleanor Marx-Aveling Story Type: From Relief to Disaster

Flaubert’s story begins with the mood of a bored and unfaithful housewife: Our main character Emma Bovary’s life has been so bad until that moment that she plunges into deep dreams that her remaining life could be better. But things don’t actually turn out that way. Emma embarks on unsuccessful and disastrous love adventures, but all these relationships provide her with only a temporary escape from the irritating reality of being married to the world’s dumbest man and her increasingly mounting debts, and eventually, Emma commits suicide by ingesting arsenic. Her husband, in pain, discovers all her betrayals, and he dies too. The grandmother to whom they sent their adopted daughter also dies. The little girl ends up going to her poor aunt, who later sends her to work in cotton factories. This is a tragedy book that has a ruthlessly descending flow aimed at a sharp fall, and a quite complete story.

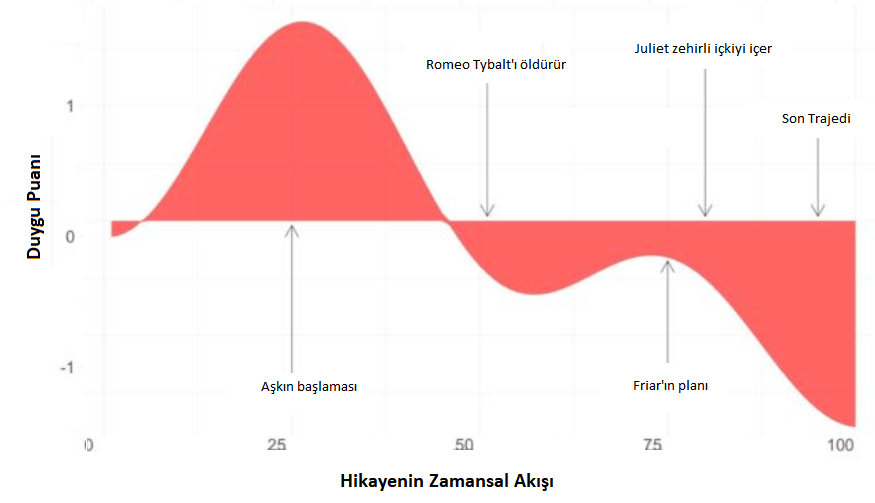

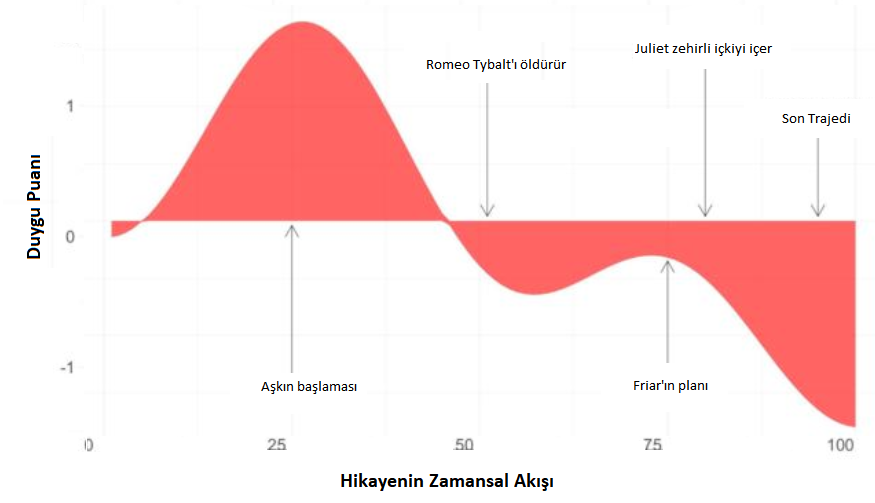

Romeo and Juliet (William Shakespeare, 1597)

Story Type: Icarus

Romeo and Juliet is considered a pure tragedy, as Shakespeare himself expressed. However, when you analyze the emotions in the work, the story reveals more of an ‘Icarus’ shape: a rise followed by a fall. In this way, the protagonist finds a woman, falls madly in love with her before they somehow lose each other. This romantic moment occurs in the famous balcony scene in the first quarter of the play, where the couple confesses their eternal love for one another. After this, the fall begins. Romeo kills Tybalt and flees, and the Friar’s plan to secretly take Juliet to him creates a false hope that leads to the drama, and from the moment Juliet drinks the poison, nothing can change the heart-wrenching tragic ending.

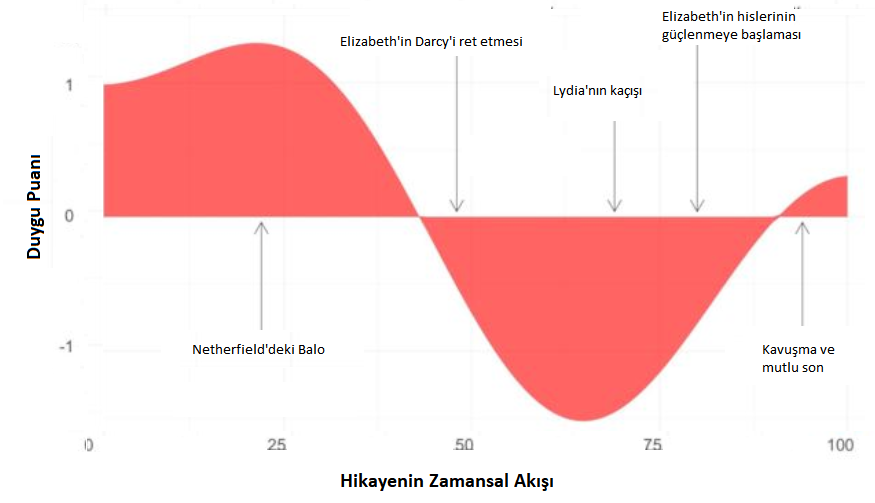

Pride and Prejudice (Jane Austen, 1813) Story

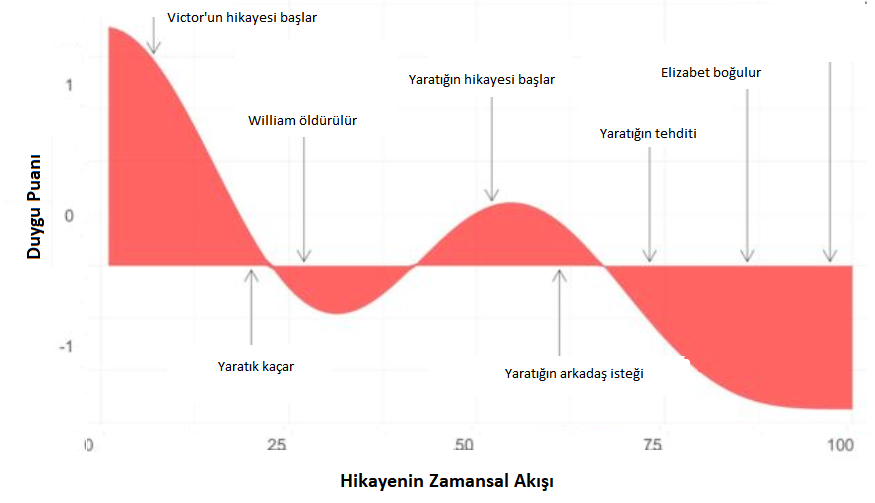

Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818)

Story Type: Oedipus

Shelley’s cult novel begins with a series of letters sent by Captain Walton to his sister and continues by telling the tragic story of Victor Frankenstein in his own words. However, at one point in the story, the Creature takes the microphone and creates another story within the story. This moment serves as a positive breath between the general emotional decline experienced since the beginning of Victor’s happy times and the horrifying conclusion of the narrative. In a pivotal scene that occurs about two-thirds of the way through the story, the Creature proposes a solution to Victor by asking him to create a female companion. However, Victor refuses. From this point on, Victor’s fate is sealed. The Creature threatens Victor by saying, “You will see, I will be with you on your wedding day.” Ultimately, he proves this.

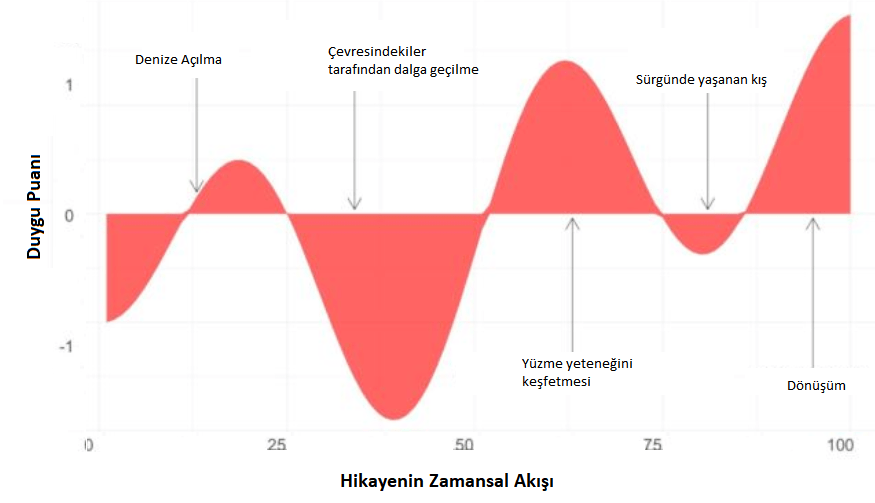

The Ugly Duckling (Hans Christian Andersen, 1843), Translation: HP Paul

Story Type: Mixed

Hans Christian Andersen’s famous fairy tale, the shortest yet most complex of all, tells the story of two heroes in a dead end (or the duckling in a dead end) and generally follows an emotional flow from bad luck to good. Although things generally improve throughout the story, there are ups and downs along the way. The duckling ventures into the sea (hooray!), but is constantly mocked by others for being different (boo!). Eventually, our hero experiences events that hint at being related to the swans wandering around, discovering that he can actually swim better than the other ducks (hooray!), but then faces death in the winter cold (boo!). As mentioned at the beginning of the story, he ultimately transforms into a swan. The underlying message here is: “As long as one hatches from a swan’s egg, being born in a duck’s nest in a farm does not prevent it from being a bird.” The story culminates in the swan’s tearful words: “He had never dreamed of such happiness.”

(EN) (TR) (ES)

Edebiyatın Matematiği

Yazı dediğimiz şey çok da eski bir icat değil. Hani imkanımız olsa da şu ana kadar yazdığımız tüm roman, hikaye, şiir, kutsal kitap, blog yazıları gibi envai çeşit içeriği bir havuza toplasak ve nelerden, nasıl ve ne sıklıkla bahsetmişiz incelesek ne bulurduk?

Bunca yıl boyunca sürekli 3-5 konuyu pişirip pişirip sunduk mu? Kült olarak adlandırdığımız edebi eserlerin arkasında yatan modellenebilir bir olay örgüsü mü var? Yani oldu da bu modeli keşfedersek, bir şekilde biz de ‘başarılı’ bir eser üretebilir miyiz? Ya da 1917 Rus Bolşevik Devrimi’nden önce peydah olan Rus Biçimci edebiyat kuramcılarının (Roman Jakobson, Osip Brik, Yuri Tinyanov gibi) iddia ettiği gibi, edebiyat denen şey mistik bir üretim tarzı değil, bilhassa kendine özgü yasaları, yapıları ve modelleri olan bir olgu muydu? Yani Shakespeare Romeo ve Juliet’i yazmasaydı da başka biri bir şekilde çıkıp buna benzer etki bırakacak bir şeyi benzer bir modele dayanarak yazabilir miydi?

Konu geniş.

Yukarıdaki sorulara ikna edici bir cevaplar vermek de zor iş.

Ancak irili ufaklı denemeler yok değil. Son zamanların moda kavramlarından ‘Büyük Veri’ ve ‘Veri işleme’ gibi alanlarla yapılan çalışmalar bu sorularla uğraşıyor. Sadece edebiyat odaklı analizler değil, genel olarak insana dair pek çok davranışın altında yatan modelleri keşfetmek, gerek sosyal bilimlerde gerekse pazarlama alanında hayli gözde. R ya da Pyhton gibi programlar yardımıyla, sosyal medya paylaşımları, orada buradaki tüketici davranışları, Google aramaları filan derken envai çeşit konuda araştırma mevcut.

Ancak konu kitaplar ve edebiyat olunca akla ilk Google vesilesi ile dijitalleştirilen basılı kitapların analizini son bir kaç yüzyıl bazında yapabileceğimiz Ngram uygulması geliyor. Ngram ile, bazı kelimelerin kitaplar içindeki kullanımının zaman içerisinde nasıl değiştiğine dair bazı gözlemler elde etmek mümkün. Mesela ben de keyfi bir iki kelime seçtim ve onların 1800-2018 yılları içerisinde Google tarafından dijital ortama aktarılmış kitaplar içindeki dağılımı aşağıdaki gibi .

Özgürlük kelimesine bakalım misal. Her iki Dünya Savaşı sonrasında bu kelimenin kullanımında bir sıçrama yaşanıyor (haliyle). Ne yazık ki 1980’lerden sonra özgürlük kelimesi, edebi gündemdeki yerini kaybediyor. 2000’lerden sonraki akışa baktığımızda, korku, eğlence ve mutluluk kelimelerinin kullanımındaki bir artış görürken, özgürlük kelimesinin bu devinimde ölü taklidi yapmasına tanık oluyoruz. Tabii ki bu basit gözlem çok da bir anlam ifade etmiyor. Entelektüel anlamda küçük oyuncaklar şu aşamada.

Ama aşağıdaki makale, çeşitli araştırmacıların, bizzat belli başlı edebi ürünlerin (ya da Gutenberg Projesi gibi çevrimiçi ve ücretsiz platformlar aracılığı ile onbinlerce kitabın) içeriğini incelemesini konu alıyor.

Ama aşağıdaki makale, çeşitli araştırmacıların, bizzat belli başlı edebi ürünlerin (ya da Gutenberg Projesi gibi çevrimiçi ve ücretsiz platformlar aracılığı ile onbinlerce kitabın) içeriğini incelemesini konu alıyor.

Ngram’daki gibi eserler içinde kelimenin salt kullanım sıklığını analiz etmekten ziyade, burada daha ilginç bir yöntem kullanılıyor. Kelimelerin tek tek duygu skalasındaki yeri belirleniyor (olumlu duygu çağrıştıran kelimeler (+) , olumsuzlar (-) skalada görece bir puan alıyor). Sonrasında kelimelerin kitap akışı içinde kullanım sıklığının değişmesi kaynaklı, kitabın zaman-ortalama duygu puanı eksenli bir modeli çıkıyor.

Bilimsel anlamda böyle bir modelleme yapılır ya da yapılmaz bir yana, film ve kitap endüstrisinin yazarları ve yönetmenleri ‘başarısı’ ispatlanmış içerik ve olay akışları doğrultusunda ürünler vermeye zorladığı ve endüstriyi bizzat bu kalıpları takip etmesi için fonladığı da bilinen bir gerçek. Sözü çok da uzatmadan, Miriam Quick’e verelim:

Yazılmış her hikaye şu 6 olay örgüsünden birine sahip

25 Mayıs, 2018, Miriam Quick, www.bbc.com

Kurt Vonnegut Antropoloji üzerine yazdığı master terzini ‘Kültüre en güzel katkım‘ şeklinde tanımlıyor, ve devam ediyor ‘ki kendisi çok basit ve eğlenceli olduğu için reddedildi’. Tez iz bırakmadan yok olmuş olsa da, Vonnegut hayatı boyunca tezinin dayandığı temel iddiayı dilinden düşürmemeye devam etti. İddia şuydu: ‘Hikayeler kareli bir kağıt üzerinde resmedebilinecek bazı yapılara sahiptir’

1995 yılındaki bir dersinde, Vonnegut tahta üzerine ana kahramanın kaderinin yazı boyunca bir eksen üzerinde ‘iyi’ den ‘kötü’ ye doğru nasıl değiştiğine dair çeşitli hikaye eğrileri çiziyor. Bu eğriler, ana karakterin başının bir belaya bulaşıp kurtulduğu (‘insanlar bu tip hikayeleri sever ve bundan asla sıkılmazlar’) ‘kahraman çıkmazda’ ya da ana kahramanın çok kıymetli bir şeyi elde ettiği, ardından kaybettiği, ve nihayet onu hikayenin sonunuda tekrar kazandığı ‘oğlan kızı kaptı’ gibi akışları içerir. ‘Bu basit hikaye eğrilerini neden bilgisayarda modellemediğimizin cevabı yok‘ diyor Vonnegut ve ekliyor: ‘Gerçekten de epey güzel eğriler bunlar’.

Neyse ki, metin madenciliği teknikleri sayesinde, Vonnegut’un bu isteği yerine getirildi. Nebraska Üniversitesi’nden Profesör Mathhew Jockers, ve sonrasında Vermont Üniversitesi’nin ‘Computational Story Lab’ araştırmacıları, binlerce romandaki veriyi analiz ederek epey karmaşık hikayelerin yapısını oluşturan 6 temel hikaye türünü, bunlara arketipler de diyebilirsiniz, ortaya çıkardılar. Vermontlu araştırmacılar, 1700 civarı ingiliz romanının arkasındaki bu 6 hikaye tipini şöyle tanımladılar:

- Felaketten feraha – Kötü talihten iyisine doğru kademeli bir yükselme

- Ferahtan Felakete – İyiden kötüye doğru bir düşüş, bir trajedi

- Ikarus – Talihin önce gülmesi ve sonrasında gerisin geriye düşüş

- Odipus – Önce bir düşüş, sonra yükseliş ve tekrar düşüş

- Külkedisi Hikayesi – Yükseliş, düşüş, yükseliş

- Kahraman Çıkmazda – Düşüş ve yükseliş

Araştırmacılar veriyi elde ederken duygu analizi tekniğini kullandı. Bu teknik daha çok pazar araştırmacıları tarafından sosyal medya paylaşımlarını analiz ederken tercih ediliyor, öyle ki her kelime kitle kaynaklı veriye dayanan belirli bir ‘duygu puanına’ denk geliyor. Tercih edilen sözlüğe göre, bir kelime, olumlu (mutlu) veya olumsuz(mutsuz), ya da korku, neşe, sürpriz ya da beklenti gibi belli başlı sekiz duygudan bir ya da bir kaçına denk geliyor. Örneğin, ‘mutlu’ kelimesi olumlu olup, neşe, güven ve beklenti duygularına denk geliyor. ‘Ortadan kaldırmak’ kelimesi ise olumsuz olup, nefret duygusu ile ilişkileniyor.

Bir roman, şiir ya da oyundaki tüm kelimeleri duygu analizi tekniği ile inceleyerek ve sonuçların haritasını zaman bir boyut olacak şekilde çıkarmak suretiyle, bir yazı içindeki duygu değişimlerini, yani yazının bir çeşit duygusal anlatısını çıkarmak mümkün oluyor. Bu yöntem, kelimelerin kendi anlamlarına odaklanıp, onları bağlam içinde değerlendirmediği için her ne kadar mükemmel olmasa da, veri bilimcisi Julia Silge’nin Jane Austen romanlarını analiz ettiği blog paylaşımında da görüldüğü gibi, bu teknik, büyük ölçekteki metinlere uygulandığında şaşırtıcı derece bilgilendirici olabiliyor. Duygu analizinin yapılabileceği araçlara ücretsiz olarak erişilebilinir ve dahası bir çok edebi eser Gutenberg Projesi gibi çevrimiçi depolama alanlarından telif hakkı sorunu olmadan indirilebilinir. Biz de, BBC Kültür’ün Dünyayı Değiştiren 100 Hikaye adlı anketindeki en çok sevilen eserleri inceleyerek bu 6 tip hikaye türünü bulmaya çalıştık.

İlahi Komedya (Dante Alighieri, 1308-1320)

Çeviri: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Hikaye Tipi: Felaketten Feraha

(Not: Tüm grafikler Miriam Quick tarafından, R programının Syuzhet, Tidytext ve Gutenbergr paketleri kullanılarak hazırlanmıştır. Tüm grafiklerde yumuşatılmış veri kullanmıştır)

(Not: Tüm grafikler Miriam Quick tarafından, R programının Syuzhet, Tidytext ve Gutenbergr paketleri kullanılarak hazırlanmıştır. Tüm grafiklerde yumuşatılmış veri kullanmıştır)

Dante’nin yoğun yapılı ve zarif bir simetriye sahip şiirsel destanının ‘Cehennem’ bölümünde, Dante’nin hayali yolculuğunda Şair Virgil -başka kim olacak- ile birlikte ölüler diyarına doğru iniyoruz. Haliyle, İlahi Komedya’nın başında işler kötü başlıyor, duygu puanı düşük, sonrasında kahramanımız cehennemin katlarında aşağıya doğru indikçe bu puan daha da düşüyor (Burada ‘Kahraman Çıkmazda’ tarzı bir akışın izleri görülüyor, öyle ki bu durum böylesi mecazi bir yazıda kelimenin tam anlamıyla doğru).

Cehennemde mucizevi bir şekilde hayatta kalmayı başardıktan sonra, kahramanlarımız şehvetli, hımbıl ve aforoz edilmiş ruhların ikamet ettiği Araf Tepesi’ne tırmanmaya başlıyor, ve nihayet Dante’nin ideal kadını olan Beatrice bu eşlik ediş sürecinde Virgil’in yerini alıyor. Şair, erdemin özünü anlayıp ruhu ‘aşk ki güneşi ve diğer yıldızları döndüren şeydir‘ ile bir olurken, bu çift, Cennet bölümünde yeryüzüne doğru çıkışa geçiyorlar ve içleri giderek artan bir neşe ile doluyor.

Madame Bovary (Gustave Flaubert, 1856)

Çeviri: Eleanor Marx-Aveling

Hikaye Tipi: Ferahtan Felakete

Flabuert’in hikayesi sıkılmış ve sadakatsiz ev hanımının ruh hali ile başlar: Ana kahramanımız Emma Bovary’ın o ana kadar yaşadığı hayat öylesine kötüdür ki, kendisi kalan yaşamının daha güzel olabileceğine dair derin hayallere dalar.

Ama işler gerçekte öyle olmaz.

Emma, başarısız ve perişan aşk maceralarına girişir, ancak tüm bu ilişkiler ona sadece dünyanın en aptal erkeği ile evli hayalperest bir kadın olmasının ve giderek artan borçlarının yarattığı can sıkıcı gerçekliğinden dönemsel bir kaçış imkanı sağlar, ve neticede Emma kendisini arsenik içerek öldürür. Acı içindeki kocası rahmetli eşinin tüm bu ihanetlerini keşfeder, ve o da ölür. Evlat ettikleri kızlarınının gönderildiği büyükanne de ölür. Küçük kız, onu sonrasında pamuk fabrikalarında çalışmaya gönderen fakir halasının yanına gider. Bu, sonunda keskin bir düşüşü amaçlayan acımasız bir akışa sahip bir trajedi kitabı ve oldukça bütün bir hikayedir.

Romeo and Juliet (William Shakespeare, 1597)

Hikaye Tipi: Ikarus

Romeo ve Juliet, Shakespeare’nin kendisinin de ifade ettiği gibi, katışıksız bir trajedi olarak kabul edilir. Fakat, eserdeki duyguları analiz ettiğinizde, hikaye daha çok ‘Ikarus’ tarzı bir şekil ortaya çıkar: Önce bir yükseliş, sonra düşüş. Öyle ki, esas oğlan bir kadın bulur, birbirlerini bir şekilde kaybetmeden evvel de ona delicesine aşık olur. Bu romantik an, oyunun ilk çeyreğinde çiftin birbirlerine olan ölümsüz aşklarını itiraf ettikleri meşhur balkon sahnesinde meydana gelir. Bundan sonra düşüş başlar. Romeo, Tybalt’ı öldürüp kaçar ve Juliet’i gizlice yanına almayı düşündüğü Friar planı ufak bir sekteye uğrar ve dramaya yol açacak yanlış bir umut yaratır ve öyle ki, Juliet’in zehri içtiği andan itibaren iç dağlayan hazin sonu değiştirecek hiç bir şey yoktur artık.

Aşk ve Gurur (Jane Austen, 1813)

Hikaye Tipi: Çıkmazdaki kahraman ya da Külkedisi Hikayesi

Austen’in büyüleyici romanının ilk yarısı baloların şenlik ve cümbüş (kısıtlı da olsa) ve tuhaf mizaçlı papaz yardımcısı Mr. Collins’in espri ile karışık gayri ciddi evlilik tekliflerinden oluşur. Bingley’in ayrılışı ve Elizabeth’in Darcy’e karşı hissetmeye başladığı tiksinti ile (elbette yanlış anlaşılmalardan ötürü oluşan) işler giderek karamsarlaşmaya başlar. Romanın duygusal akışı, Darcy’nin başarısız evlilik teklifinin ardından negatif bölgeye doğru evrilir ve Lydia’nın tekinsiz Wickham ile kaçışı ile de dibi görür. Bu durum Darcy’nin kendisini kanıtlaması için de bir fırsat yaratır, öyle ki O da bu fırsatı büyük bir onur ve ağırbaşlılıkla kullanır ve neticede Elizabeth’in kalbini elde ederek, herkesin eskine nazaran biraz daha erdemli olduğu bir mutlu son’u yaratmış olur.

Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818)

Hikaye tipi: Odipus

Shelly’in kült romanı, Kaptan Walton’un kız kardeşine gönderdiği mektup serisi ile başlar ve Victor Frankenstein’ın üzücü hikayesini Victor’un kendi ağzından anlatarak devam eder. Ancak hikayenin bir noktasında, Yaratık mikrofonu eline alarak hikayenin içinde başka bir hikaye yaratır. Öyle ki, bu ara, Viktor’un hayatının mutlu zamanlarını anlatarak başladığı hikayenin ilk kısmından itibaren yaşanan genel duygusal düşüş ile dehşet verici son arasında yaşanan olumlu bir soluk alma gibidir. Hikayenin üçte ikisine yakın bir yerde yaşana can alıcı bir sahnede, Yaratık, Viktora’dan ona kadın bir yol arkadaşı yaratmasını isteyerek Viktor’a bir çözüm yolu önerir. Ancak Viktor bunu kabul etmez. Bu noktadan sonra, Viktor’un kaderi çizilmiştir artık. Yaratık, ‘ Göreceksin, senin düğün gününde seninle birlikte olacağım‘ diyerek Viktor’u tehdit eder. Neticede bunu kanıtlar da.

Çirkin Ördek Yavrusu (Hans Christian Andersen, 1843)

Çeviri: HP Paul

Hikaye tipi: Karışık

Hepsi içinde en kısa ama aynı zamanda en karmaşık yapıya sahip olan Hans Christian Andersen’ın ünlü masalı, çıkmazda olan iki kahramanın hikayesini (ya da çıkmazdaki ördeğin) konu alır ve duygusal akış genel olarak kötü talihten iyisine doğru şekillenir. Öyle ki, işler hikayenin akışı içinde genel olarak iyiye gitse de, ara ara iniş çıkışlar yaşanır. Ördek denize açılır (yaşasın!), ancak çevresindekiler tarafından farklı olduğu için sürekli kendisi ile dalga geçilinir (ühü!). Sonunda aslında diğer ördeklerden daha iyi yüzebildiğini keşfeden kahramanımız etrafta dolaşan kuğular ile bir şekilde akraba olduğuna dair bir şeyler sezmesini sağlayan olaylar yaşar (yaşasın!), fakat kış soğuğunda ölümle yüzyüze gelir (ühü!). Hikayenin en başında da söylendiği üzere, neticede kendisi bir kuğuya dönüşür. Elbette buradaki mesaj şudur: ‘ Bir kuğunun yumurtasından çıktığı müddetçe, çiftlik içindeki bir ördek yuvasında doğmak onun bir kuş olmasına bir engel oluşturmaz‘. Hikaye kuğunun göz yaşları içindeki şu sözleri ile zirveye ulaşır: ‘hiç bir zaman böylesine bir mutluluk hayal edememişti’

Orijinal metin burada

(EN) (TR) (ES)

La Matemática de la Literatura

La escritura no es un invento tan antiguo. Si tuviéramos la oportunidad de recopilar en un solo lugar todas las novelas, cuentos, poemas, libros sagrados y publicaciones de blog que hemos escrito hasta ahora, ¿qué encontraríamos al examinarlas? ¿Hemos estado constantemente cocinando y sirviendo 3-5 temas durante todos estos años? ¿Hay una trama modelable detrás de las obras literarias que llamamos cultas? Es decir, si descubrimos este modelo, ¿podríamos de alguna manera producir también una obra ‘exitosa’? O, como afirmaron los teóricos rusos del formalismo literario que surgieron antes de la Revolución Bolchevique de 1917 (como Roman Jakobson, Osip Brik, Yuri Tinyanov), ¿es la literatura un modo de producción místico, o más bien un fenómeno con leyes, estructuras y modelos propios? Es decir, ¿si Shakespeare no hubiera escrito “Romeo y Julieta”, podría otra persona haber escrito algo similar que tuviera un efecto similar basado en un modelo similar?

El tema es amplio. Es difícil dar respuestas convincente a las preguntas anteriores. Sin embargo, no faltan ensayos de diferentes tamaños. Trabajos en áreas como ‘Big Data’ y ‘procesamiento de datos’, que son conceptos de moda en los últimos tiempos, abordan estas preguntas. No solo se trata de análisis enfocados en la literatura, sino que descubrir los modelos subyacentes a muchos comportamientos humanos es bastante popular tanto en ciencias sociales como en marketing. Con la ayuda de programas como R o Python, existe investigación sobre una variedad de temas, desde publicaciones en redes sociales hasta comportamientos de consumo y búsquedas en Google.

Sin embargo, cuando se trata de libros y literatura, lo primero que viene a la mente es la aplicación Ngram, que nos permite analizar libros impresos digitalizados a través de Google en los últimos siglos. Con Ngram, es posible obtener observaciones sobre cómo ha cambiado el uso de ciertas palabras en los libros a lo largo del tiempo. Por ejemplo, elegí un par de palabras al azar y su distribución en los libros digitalizados por Google entre 1800 y 2018 es la siguiente.

Tomemos la palabra “libertad” como ejemplo. Después de ambas Guerras Mundiales, hay un salto en el uso de esta palabra (como era de esperar). Lamentablemente, después de los años 80, la palabra “libertad” pierde su lugar en la agenda literaria. Al observar la tendencia después de los años 2000, mientras vemos un aumento en el uso de palabras como miedo, entretenimiento y felicidad, somos testigos de que “libertad” hace una especie de simulacro de muerte en este movimiento. Por supuesto, esta observación simple no tiene mucho significado. En términos intelectuales, son pequeños juguetes en esta etapa.

Sin embargo, el artículo a continuación trata sobre cómo varios investigadores han analizado el contenido de obras literarias específicas (o decenas de miles de libros a través de plataformas en línea y gratuitas como el Proyecto Gutenberg). En lugar de simplemente analizar la frecuencia de uso de la palabra en las obras como en Ngram, aquí se utiliza un método más interesante. Se determina la ubicación de cada palabra en la escala de emociones (las palabras que evocan emociones positivas reciben un puntaje (+), y las negativas (-)). Posteriormente, se genera un modelo basado en cómo cambia la frecuencia de uso de las palabras en los libros, con un puntaje emocional promedio en el tiempo.

Independientemente de si se puede o no hacer tal modelado en un sentido científico, es un hecho conocido que los autores y directores de la industria del cine y la literatura están obligados a ofrecer productos en función de contenidos y tramas cuya ‘éxito’ ha sido probado, y que se financia a la industria para que siga estos patrones. Sin extender demasiado la palabra, dejemos que Miriam Quick tome la palabra:

Cada historia escrita tiene una de estas 6 tramas. 25 de mayo de 2018, Miriam Quick, www.bbc.com Kurt Vonnegut define su tesis de maestría sobre antropología como ‘mi mejor contribución a la cultura’, y continúa: ‘porque fue tan simple y divertida que fue rechazada’. Aunque la tesis desapareció sin dejar rastro, Vonnegut siguió defendiendo la idea fundamental en la que se basaba durante toda su vida. La afirmación era: ‘Las historias tienen ciertas estructuras que pueden representarse en un papel cuadriculado’.

En una lección de 1995, Vonnegut dibuja en la pizarra varias curvas de historia que ilustran cómo el destino del protagonista cambia a lo largo de la escritura en un eje de ‘bueno’ a ‘malo’. Estas curvas incluyen tramas donde el protagonista se mete en problemas y logra escapar (‘a la gente le encantan este tipo de historias y nunca se cansan de ellas’), así como ‘el héroe en apuros’, o el flujo donde el protagonista obtiene algo valioso, lo pierde y finalmente lo vuelve a ganar al final de la historia (‘el chico se queda con la chica’). ‘No hay respuesta a por qué no modelamos estas simples curvas de historia en la computadora’, dice Vonnegut, y agrega: ‘Realmente son curvas muy bonitas’.

Afortunadamente, gracias a las técnicas de minería de texto, se ha cumplido el deseo de Vonnegut. El profesor Mathhew Jockers de la Universidad de Nebraska, y posteriormente los investigadores del ‘Computational Story Lab’ de la Universidad de Vermont, descubrieron seis tipos básicos de historias que constituyen la estructura de historias bastante complejas analizando datos de miles de novelas. Los investigadores de Vermont definieron estos 6 tipos de historias en las novelas inglesas de alrededor de 1700 de la siguiente manera:

De la desgracia a la felicidad – Un aumento gradual de la mala suerte a la buena De la felicidad a la desgracia – Una caída de lo bueno a lo malo, una tragedia Ícaro – La suerte sonríe al principio y luego desciende de nuevo Edipo – Primero una caída, luego un ascenso y otra caída Historia de Cenicienta – Ascenso, caída, ascenso Héroe en apuros – Caída y ascenso

Los investigadores utilizaron la técnica de análisis de sentimientos para obtener datos. Esta técnica es preferida más por los investigadores de mercado al analizar publicaciones en redes sociales, de tal manera que cada palabra corresponde a un ‘puntaje emocional’ específico basado en datos de crowdsourcing. Según el diccionario preferido, una palabra puede ser positiva (feliz) o negativa (triste), o puede corresponder a una o más de las ocho emociones principales como miedo, alegría, sorpresa o expectativa. Por ejemplo, la palabra ‘feliz’ es positiva y corresponde a las emociones de alegría, confianza y expectativa. La palabra ‘eliminar’ es negativa y se relaciona con la emoción de odio.

Al examinar todas las palabras en una novela, poema o obra de teatro mediante la técnica de análisis de sentimientos y generar un mapa de resultados con el tiempo como dimensión, es posible extraer los cambios emocionales en un texto, es decir, la narrativa emocional de un escrito. Este método, aunque no sea perfecto porque no se centra en los significados de las palabras y no las evalúa en su contexto, como muestra el blog de la científica de datos Julia Silge que analizó las novelas de Jane Austen, puede ser sorprendentemente informativo cuando se aplica a textos a gran escala. Hay herramientas disponibles gratuitamente para realizar análisis de sentimientos, y además, muchas obras literarias se pueden descargar sin problemas de derechos de autor desde espacios de almacenamiento en línea como el Proyecto Gutenberg. También intentamos identificar estos 6 tipos de historias al examinar las obras más queridas en la encuesta de BBC Cultura sobre las 100 historias que cambiaron el mundo.

Divina Comedia (Dante Alighieri, 1308-1320) Traducción: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Tipo de Historia: De la Desgracia a la Felicidad (Nota: Todos los gráficos fueron preparados por Miriam Quick utilizando los paquetes Syuzhet, Tidytext y Gutenberg del programa R. Todos los gráficos utilizan datos suavizados.)

En la sección ‘Infierno’ de la densa y poética obra de Dante, descendemos al reino de los muertos junto al poeta Virgilio -¿quién más?- en su viaje imaginario. Como era de esperar, las cosas comienzan mal en la Divina Comedia, con un bajo puntaje emocional, y a medida que nuestro héroe desciende por los círculos del infierno, este puntaje disminuye aún más (Aquí se pueden observar los rastros de una narrativa estilo ‘héroe en apuros’, ya que en una obra de tal naturaleza, esto es literalmente correcto). Después de sobrevivir milagrosamente en el infierno, nuestros héroes comienzan a ascender hacia la colina del Purgatorio, donde finalmente Beatriz, la mujer ideal de Dante, reemplaza a Virgilio en este proceso de acompañamiento. El poeta, al comprender la esencia de la virtud y unirse con el alma en ‘el amor que mueve al sol y las otras estrellas’, asciende junto a Beatriz hacia el Paraíso y se llena de una alegría creciente.

Madame Bovary (Gustave Flaubert, 1856) Traducción: Eleanor Marx-Aveling Tipo de Historia: De la Felicidad a la Desgracia

La historia de Flaubert comienza con el estado de ánimo de una ama de casa aburrida y adúltera: nuestra protagonista, Emma Bovary, está tan sumida en sueños de que su vida podría ser más hermosa que la vida que .realmente lleva, que siente una profunda insatisfacción. A medida que avanza la historia, la búsqueda de Emma de un amor idealizado y una vida emocionante la lleva a tomar decisiones trágicas que la llevan a la ruina. Su felicidad inicial se transforma en desilusión y desesperación, lo que culmina en un desenlace trágico. A lo largo de la novela, el puntaje emocional de Emma cae drásticamente, ilustrando su transición de la felicidad a la desgracia.

Orgullo y prejuicio (Jane Austen, 1813) Traducción: Emma Thompson Tipo de Historia: Historia de Cenicienta

La obra de Austen narra la historia de Elizabeth Bennet, una mujer inteligente y fuerte en un mundo dominado por normas sociales restrictivas. La relación entre Elizabeth y Mr. Darcy evoluciona desde el desdén mutuo hacia una profunda conexión amorosa. Al inicio, la narrativa muestra un puntaje emocional bajo, reflejando las tensiones y malentendidos entre los personajes. Sin embargo, a medida que la historia avanza, el amor y la comprensión reemplazan la hostilidad inicial, llevando a un desenlace feliz y un ascenso emocional, lo que se alinea con el tipo de historia de Cenicienta.

Yorum bırakın