(EN) (TR) (ES)

The 18th Century

The Industrial Revolution is bustling. The countryside of England has turned a bluish-gray, and factories are producing not only consumer goods but also a new concept known as the masses.

Colonialism is at its most fervent century. A flood of “wealth” is pouring into Europe from its “colonies” or, to put it more naively, from the “places it has discovered.”

On one side are factories, and on the other side is the “wealth” coming from the colonies, making life cheaper in many ways.

As a result, the notion of “consumption” in people’s minds is also undergoing a transformation: the vicious cycle of consuming without producing begins to sit at the core of social life, much like in the consumption of the aristocracy, starting to establish itself upon “social identity.” This wealth, once reserved for a handful of minorities, is gradually spreading to the bourgeoisie, middle, and lower classes.

The wealth we speak of is not just gold, silver, diamonds, or lavish silk garments; it includes various products like coffee, tea, spices, and pineapples, which have firmly established themselves as ordinary items in our daily lives.

Thus, the consumption habits of the upper class, which spent their time consuming specific things and proved their social roles in this manner, are, one way or another, becoming accessible to the rest of society. As was popular in that era, the essence lies in human rights and equality, leading to the democratization of consumption.

Diderot’s Books

While the general atmosphere in Europe is like this, in the 1760s, the French romantic, humanist, and Enlightenment thinker Denis Diderot also flounders within this current before ultimately finding himself in financial straits.

As soon as the famous Russian empress Catherine hears about his situation, she purchases Diderot’s “wealthy” library. She also appoints Diderot as a librarian in her own library for a period of 25 years.

Naturally, Diderot’s spirits are lifted upon finding the money he craved.

He quickly makes a shift to the consumption fashion of the era: new jewelry, nightgowns, lavish furniture, and exotic foods, and before long, the money starts to dwindle.

Diderot soon begins to lament once more, feeling both hungry and exposed. Like every normal Sapiens, he starts to question the mistakes that brought him to this point and uncovers interesting truths about his insatiable consumption habits.

The Diderot Effect

Centuries have passed since Diderot discovered these interesting aspects of his consumption habits; nonetheless, the consumption fashion he lamented in pain shows no signs of fading away.

On the contrary, what began as a consumption fashion in Europe has transformed into a type of “reality” and a normalized “lifestyle” that has spread worldwide. So much so that it is almost impossible for contemporary individuals to envision a world without consumption centered around social status.

Consumption has evolved from merely meeting our needs to becoming a chaotic entity that defines and proves our lives, identities, and social roles, increasing the number of researchers studying the subject.

One of these researchers is anthropologist Grant McCracken.

Drawing from Diderot’s self-analysis, he introduces a new and interesting concept to the literature regarding human behavior concerning consumption “addiction”:

The Diderot Effect

McCracken’s Diderot effect explains the human behavior that traps individuals in a vicious cycle of consumption in two dimensions:

- The things we buy become a part of our character, and each item we acquire complements the others we possess.

- If the newly acquired item somehow doesn’t fit our identity, we purchase something new to fill that gap.

As can be understood from these lines, what ultimately led Diderot to bankruptcy was not merely his consumption but rather entering a vicious cycle of consumption.

The newly acquired mahogany desk is designed to suit an intellectual like him and matches perfectly with the pattern of his inkpot. However, while sitting in a delightful pair of armchairs with lion feet that he bought at an auction in Lyon, wearing his favorite blue silk dressing gown, he feels a sense of unease. Although the nightgown and the armchairs create a lovely harmony, he feels completely attached to these objects and the bohemian atmosphere they create; yet there’s that new desk! It’s a complete dissonance! He must change it or buy a new one. Or perhaps he should change the dressing gown and the chair. Maybe the problem isn’t the desk, but the walnut color of the chair doesn’t match the colors of the armchairs. Or perhaps the real issue is the green velvet curtains in the back…

Diderot’s vicious cycle of consumption addiction is not just a common problem for the enriching middle classes of the 18th century or the baronial families; it is also a sweet curse of contemporary individuals. It brings along dissatisfaction, ambition, depression, meaninglessness, narcissism, and social disconnection, filling our lives with a frenetic and shameless hustle. One cannot help but ponder the reaction of such an enlightened figure as Diderot to this “effect” that led to a life filled with chaos and regrets.

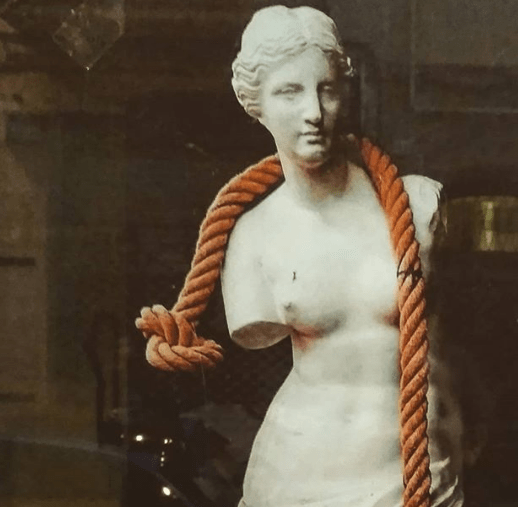

Ultimately, deriving aesthetic pleasure from objects and actions is an immense wealth for human nature. Unfortunately, one doesn’t need to be a genius or an intellectual to see that an aesthetically sickly attachment to “I consume, therefore I am” will bring more regret than pleasure. The famous dressing gown of Diderot, because it connects aesthetics and consumption through an organic link, traps not just consumption but life itself in a vicious cycle.

It seems that instead of chasing after the reckless satisfaction of the false needs we create through our social status, we can break this vicious cycle by recognizing ourselves and our needs and consuming what truly defines us.

Perhaps a productive cycle lies in consumptions where production and aesthetics merge.

References

McCracken, Grant. Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1988; pp. 118–129.

Schor, Juliet B. The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need. Harper Perennial; 1st HarperPerennial Ed Pub. 1999 edition.

‘Diderot Effect’. Evans, D., in: P. Robbins, J. Mansvelt and G. Golson, editor(s). Encyclopaedia of Green Consumerism. Sage; 2010.

Pantzar, Mika. Domestication of Everyday Life Technology: Dynamic Views on the Social Histories of Artifacts in Design Issues, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 52-65.

The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need

Regrets on My Old Dressing Gown

(EN) (TR) (ES)

Diderot’un geceliği

18. Yüzyıl

Endüstri devrimi kıpır kıpır. İngiltere’nin kırsalı gök mavisi grileşmiş; fabrikalar sadece tüketim nesnelerini değil, “kitle” denilen yeni bir kavramı da üretiyor.

Sömürgecilik, en hararetli yüzyılında. Avrupa’ya “sömürgelerinden” ya da daha naif bir ifade ile “keşfettiği yerlerden” akın akın “zenginlik” geliyor.

Bir yanda fabrikalar, bir yanda sömürgelerden gelen “zenginlik” derken, yaşam pek çok açıdan ucuzluyor.

Haliyle, insanların kafasındaki “tüketim” düşüncesi de değişime uğruyor: Üretmeden tüketim’in kısır döngüsü, sosyal hayatın göbeğine, tıpkı aristokrasinin tüketiminde olduğu gibi, “sosyal kimlik” üzerine oturmaya başlıyor. Daha önce bir avuç azınlığa nasip olan bu zenginlik, artık yavaş yavaş burjuva, orta ve alt tabakaya yayılıyor.

Zenginlik dediğimiz sadece altın, gümüş, pırlanta ya da şatafatlı ipek elbiseler de değil; kahve, çay, baharat, ananas gibi şimdiki zamanda gündelik hayatımıza sıradan nesneler olarak iyiden iyiye yerleşmiş bilumum ürünü de içeriyor.

Yani, zamanlarını belli başlı şeyleri tüketerek harcayan ve sosyal rollerini ancak bu şekilde ispat eden üst sınıfın tüketim alışkanlıkları, öyle ya da böyle, toplumun geri kalanının erişimine açılıyor. O dönemin popüler ifadesiyle, esas olan insan hakları ve eşitlik; haliyle, tüketimin de demokratikleşmesi.

Diderot’un Kitapları

Avrupa’daki genel hava böyle iken, 1765’li yıllarda Fransız romantik, humanist aydınlanmacı düşünür orta direk Diderot da bu akım içinde bir süre debelendikten sonra, sonunda paraya sıkışır.

Meşhur Rus kraliçesi Katerina, vaziyeti duyar duymaz Diderot’un “zengin” kütüphanesini satın alır. Aynı zamanda insaflı bir kraliçe olarak, Diderot’u da kendi kütüphanesinde 25 yıllığına memur olarak atar. Özlemini duyduğu parayı bulan Diderot’un keyfi de yerine geliyor haliyle.

Dönemin “tüketim” modasına hızlı bir dönüş yapar: Yeni takılar, gecelikler, şatafatlı mobilyalar, egzotik yemekler derken, haydan gelen para da suyunu çeker.

Diderot yine aç ve açıkta sızlanmaya başlar. Düşen her normal Sapiens gibi, o da kendisini bu noktaya getiren hatalarını sorgulamaya başlar ve iflah olmaz tüketim ilgisine dair ilginç şeyler bulur.

Diderot Etkisi

Diderot’un kendi tüketim alışkanlığı ile ilgili bulduğu ilginç şeylerin üzerinden yüzyıllar geçiyor; geçiyor geçmesine de, O’nun acı içinde şikayet ettiği tüketim modası herhangi bir yok olma eğilimi göstermiyor.

Bilakis, Avrupa’da bir dönemin tüketim modası olarak başlayan şey, tüm dünyaya yayılan bir tür “gerçeklik” ve normalleşmiş bir “yaşam şekli”ne dönüşüyor. Öyle ki, günümüz insanının kendini sosyal statü odaklı tüketim olmadan yaşadığı bir dünyayı düşlemesi neredeyse imkansız.

Tüketimin ihtiyaçlarımızı gideren bir kavram olmasından çıkıp, bizzat hayatımızı, kimliğimizi ve sosyal rollerimizi tanımlayan ve ispatlayan karmakarışık bir hale gelmesi, konu ile araştırma yapanların sayısını arttırıyor.

Antropolog Grant McCracken bunlardan biri.

Diderot’un kendi kendini analiz ettiği bu satırlardan yola çıkarak, insanların tüketim “bağımlılığı” ile ilgili literatüre yeni ve ilginç bir kavram katıyor: Diderot Etkisi. McCracken’in Diderot etkisi, kişiyi tüketimde kısır bir döngüye sokan insan davranışını iki boyutta açıklıyor:

- Satın aldığımız şeyler, karakterimizin bir parçası haline gelir ve aldığımız her nesne elimizdeki bir diğerini tamamlar.

- Oldu da yeni alınan nesne bir şekilde kimliğimize oturmazsa, bu açığı kapatmak için yeni bir şey satın alırız.

Bu satırlardan da anlaşıldığı gibi, Diderot’u iflasa sürükleyen şey, tüketmesi değil, kısır bir tüketim döngüsü içine girmesiydi.

Yeni aldığı maun çalışma masası tam da onun gibi bir entelektüele yakışır tasarımda, mürekkep kutusunun deseni ile de ölesiye uyumlu. Ancak, en çok sevdiği mavi ipek sabahlığı ile Lyon’daki bir açık artırmada aldığı leziz masif aslan ayak çift berjerinde otururken kendini huzursuz hissediyor. Üzerindeki gecelik ve berjeri enfes bir bütünlük içinde; kendini tam da bu nesnelere ve onların yarattığı bu bohem havaya ait hissediyor. Ancak şu yeni aldığı çalışma masası yok mu? Tam bir ruh detonesi! Onu değiştirmeli, yenisini almalı. Ya da üzerindeki sabahlığı ve koltuğu değiştirmeli. Belki de sorun masa değildir; masanın sandalyesinin ceviz ağacı rengi ile berjerin renkleri uyumsuzdur. Ya da esas sorun arkadaki yeşil kadife perdeler…

Diderot’un kısır tüketim bağımlılığı, sadece 18. yüzyılın zenginleşen orta direklerinin ya da yüzyıllar boyu süren Baron ailelerinin ortak sorunu değil; günümüz insanının da püsküllü bir belasıdır. Beraberinde tatminsizlik, hırs, depresyon, anlamsızlık, narsisizm ve sosyal kopuşmalar getiren, bir yanda iğreti, bir yanda arsız bir koşturma ile günümüzü dolduran tatlı bir bela. Diderot gibi bir aydının hayatını kaos ve pişmanlıklara sürükleyen bu “etki”nin bizdeki tepkisini düşünmeden edemiyor insan.

Neticede, nesne ve eylemlerden estetik bir zevk almak, insanın doğası için müthiş bir zenginliktir. Ne yazık ki “tüketiyorum, öyleyse varım” ile hastalıklı bir şekilde bağlanmış bir estetiğin hazdan ziyade pişmanlık getireceğini görmek için de dahi ya da aydın olmak gerekmiyor. Öyle ki, Diderot’un meşhur geceliği, estetik ile tüketimi organik bir bağla birleştirdiği için, sadece tüketimi değil, hayatı da kısır döngüye sokuyor.

Öyle görünüyor ki, sosyal statümüz üzerinden yarattığımız sahte gereksinimleri fütursuzca tatmin peşinde koşmakla uğraşacağımıza, kendimizi ve ihtiyaçlarımızı tanıyıp, bizi biz yapan şeyleri tüketerek o kısır döngüyü kırabiliriz.

Belki de verimli bir döngü, üretim ile estetiğin birleştiği tüketimlerde yatar.

Kaynakça

McCracken, Grant Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1988; pp. 118–129

Schor, Juliet B. “The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need” Harper Perennial; 1st HarperPerennial Ed Pub. 1999 edition.

‘Diderot Effect’Evans, D, in: P. Robbins, J. Mansvelt and G.Golson, editor(s). “Encyclopaedia of Green Consumerism”. Sage; 2010.

Pantzar, Mika “Domestication of Everyday Life Technology: Dynamic Views on the Social Histories of Artifacts” in Design Issues, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 52-65

The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need

Regrets on My Old Dressing Gown

(EN) (TR) (ES)

La bata de Diderot

El siglo XVIII

La Revolución Industrial está en plena efervescencia. El campo de Inglaterra se ha vuelto de un gris azulado, y las fábricas no solo producen bienes de consumo, sino también un nuevo concepto conocido como las masas.

El colonialismo se encuentra en su siglo más ferviente. Una avalancha de “riqueza” está llegando a Europa desde sus “colonias” o, para expresarlo de manera más ingenua, desde los “lugares que ha descubierto”.

Por un lado están las fábricas y, por el otro, la “riqueza” que llega de las colonias, haciendo que la vida sea más barata en muchos aspectos.

Como resultado, la noción de “consumo” en la mente de las personas también está experimentando una transformación: el ciclo vicioso de consumir sin producir comienza a establecerse en el núcleo de la vida social, de manera similar a lo que sucede en el consumo de la aristocracia, comenzando a asentarse sobre la “identidad social”. Esta riqueza, que antes era patrimonio de un puñado de minorías, se está extendiendo gradualmente a la burguesía, las clases medias y bajas.

La riqueza de la que hablamos no es solo oro, plata, diamantes o lujosos trajes de seda; también incluye productos diversos como café, té, especias y piñas, que se han consolidado firmemente como elementos ordinarios en nuestra vida cotidiana.

Así, los hábitos de consumo de la clase alta, que gastaba su tiempo consumiendo cosas específicas y demostrando sus roles sociales de esta manera, se están volviendo accesibles para el resto de la sociedad, de una manera u otra. Como era popular en esa época, la esencia radica en los derechos humanos y la igualdad, lo que lleva a la democratización del consumo.

Los libros de Diderot

Mientras el ambiente general en Europa es así, en los años 1760, el pensador francés romántico, humanista y de la Ilustración Denis Diderot también se debate un tiempo dentro de esta corriente antes de encontrarse finalmente en problemas financieros.

Tan pronto como la famosa emperatriz rusa Catalina se entera de su situación, compra la “rica” biblioteca de Diderot. También lo nombra bibliotecario en su propia biblioteca durante un período de 25 años.

Naturalmente, el estado de ánimo de Diderot se eleva al encontrar el dinero que tanto deseaba.

Rápidamente hace un cambio hacia la moda del consumo de la época: nuevos joyas, camisones, muebles lujosos y comidas exóticas, y antes de que se dé cuenta, el dinero comienza a escasear.

Diderot pronto empieza a quejarse de nuevo, sintiéndose hambriento y expuesto. Como cualquier sapiens normal, comienza a cuestionar los errores que lo llevaron a este punto y descubre verdades interesantes sobre sus insaciables hábitos de consumo.

El efecto Diderot

Han pasado siglos desde que Diderot descubrió estos aspectos interesantes de sus hábitos de consumo; sin embargo, la moda de consumo que lamentó en dolor no muestra signos de desvanecerse.

Por el contrario, lo que comenzó como una moda de consumo en Europa se ha transformado en una especie de “realidad” y un “modo de vida” normalizado que se ha extendido por todo el mundo. Tanto es así que es casi imposible para los individuos contemporáneos imaginar un mundo sin consumo centrado en el estatus social.

El consumo ha evolucionado de ser simplemente un concepto que satisface nuestras necesidades a convertirse en una entidad caótica que define y demuestra nuestras vidas, identidades y roles sociales, aumentando el número de investigadores que estudian el tema.

Uno de estos investigadores es el antropólogo Grant McCracken.

Partiendo del autoanálisis de Diderot, introduce un concepto nuevo e interesante en la literatura sobre el “vínculo” que las personas tienen con la “adicción” al consumo:

El efecto Diderot

El efecto Diderot de McCracken explica el comportamiento humano que atrapa a las personas en un ciclo vicioso de consumo en dos dimensiones:

- Las cosas que compramos se convierten en parte de nuestro carácter, y cada objeto que adquirimos complementa a los demás que poseemos.

- Si el nuevo objeto adquirido de alguna manera no encaja con nuestra identidad, compramos algo nuevo para llenar ese vacío.

Como se puede entender de estas líneas, lo que finalmente llevó a Diderot a la bancarrota no fue simplemente su consumo, sino más bien entrar en un ciclo vicioso de consumo.

El escritorio de caoba que acaba de adquirir está diseñado para ser adecuado para un intelectual como él y combina perfectamente con el patrón de su tintero. Sin embargo, mientras se sienta en un par de sillones con patas de león que compró en una subasta en Lyon, vistiendo su amado camisón de seda azul, siente una incomodidad. Aunque el camisón y los sillones crean una armonía encantadora, se siente completamente conectado a estos objetos y al ambiente bohemio que crean; sin embargo, hay ese nuevo escritorio. ¡Es una completa disonancia! Debe cambiarlo o comprar uno nuevo. O tal vez debería cambiar el camisón y el sillón. Quizás el problema no es el escritorio, sino que el color de la silla de nuez no combina con los colores de los sillones. O tal vez el verdadero problema son las cortinas de terciopelo verde detrás…

La adicción al consumo vicioso de Diderot no es solo un problema común de las clases medias enriquecidas del siglo XVIII o de las familias de barones; también es una dulce maldición de los individuos contemporáneos. Trae consigo insatisfacción, ambición, depresión, falta de sentido, narcisismo y desconexiones sociales, llenando nuestras vidas con una carrera frenética y descarada. Uno no puede evitar pensar en la reacción de un personaje tan ilustrado como Diderot ante este “efecto” que lo llevó a una vida llena de caos y arrepentimientos.

En última instancia, obtener placer estético de objetos y acciones es una enorme riqueza para la naturaleza humana. Desafortunadamente, no es necesario ser un genio o un intelectual para ver que un vínculo estéticamente enfermo con “consumo, por lo tanto soy” traerá más arrepentimiento que placer. El famoso camisón de Diderot, porque conecta la estética y el consumo a través de un vínculo orgánico, atrapa no solo el consumo, sino también la vida misma en un ciclo vicioso.

Parece que, en lugar de perseguir la satisfacción desenfrenada de las necesidades falsas que creamos a través de nuestro estatus social, podemos romper este ciclo vicioso reconociéndonos a nosotros mismos y a nuestras necesidades, y consumiendo lo que realmente nos define.

Quizás un ciclo productivo radica en consumos donde se combinan la producción y la estética.

Referencias

McCracken, Grant. Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1988; pp. 118–129.

Schor, Juliet B. The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need. Harper Perennial; 1st HarperPerennial Ed Pub. 1999 edition.

‘Efecto Diderot’. Evans, D., en: P. Robbins, J. Mansvelt y G. Golson, editor(es). Enciclopedia del Consumismo Verde. Sage; 2010.

Pantzar, Mika. Domesticación de la Tecnología de la Vida Cotidiana: Perspectivas Dinámicas sobre las Historias Sociales de los Artefactos en Design Issues, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Otoño, 1997), pp. 52-65.

The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need

Regrets on My Old Dressing Gown