(EN) (TR) (ES)

Modern Idols of Time: Photographs

When Kodak said in its advertisements, “We keep your memories forever,” neither our lives nor our memories had yet become so digitalized. But they kept their promise; they engraved the memories of several generations onto paper. Some were produced with great effort in red rooms, while others were sold in groups of 36 or 24 in stores. We kept the ones we liked in albums, put the ones we didn’t like into piles of photographs, and discarded production errors. In a way, we filtered memories. At times, we even organized them by importance and time, placing them into albums, writing small notes on their backs.

It was the magic of being able to materialize a memory from the past and carry it with us like an object that made them precious. Photographs were like modern idols. They were a precaution we took against the terrifying power of time that drags, ages, and destroys. Moreover, like every idol, they had a fundamental function: to share and to connect.

Here I Am, Hands

Photography is one of the relatively newer idols of this type. The human fear of time and the anxiety of missing a moment have always accompanied our existence. Think of the hands below that say, “I am here, I am present.” It’s somewhat like a modern selfie. We may not be able to see the smiling faces of our ancestors from thousands of years ago or know what they felt when they touched the wall with their hands, but we can somewhat imagine the urge that drove them to leave their handprints on the walls—the pressure of time on their backs, the feeling of existence, the desire to immortalize that moment, share it, and connect.

Over time, humans developed more complex methods than just blowing powdered paint onto a wall to leave their handprints. The images, hunts, and festivals that our ancestors drew on walls with relatively primitive methods evolved over centuries, finding a broader field of expression through painting, sculpture, and architecture.

As the relationship between daily life and time changed, a god, a battle memory, an afternoon of an aristocratic family, a portrait of a king, even a flower, a sunset, or an ordinary neighborhood market began to materialize. In that uncertainty of time, they were meticulously captured, pulled, and left in the realm of the tangible. Some were created with artistic concerns, others social, and some as a language we formed individually.

The First Photograph: The Pigeon’s Nest

Finding ways to produce objects that imply a twin of life—things that humans did not create with their own hands, namely photographs (and films)—became one of the greatest desires of inventors and scientists for centuries. Finally, in the 19th century, successful techniques related to photography were developed, and for the first time in history, humans managed to create an exact twin of the moment. It was perhaps the first great victory won against the cruelty of time. Life could be frozen or recorded as it was.

The photograph below, for example, is one of the earliest recorded photographs taken by retired Colonel Niepce on a warm summer day in Paris a few hundred years ago. It is called the Pigeon’s Nest. The colonel climbed to the top of a building and captured the image of an ordinary day and street, freezing a moment of what he saw with his own eyes. Even now, with this photograph, we can travel back to that afternoon in 1838 and see a moment copied from his perspective, disconnected from time.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE, Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 1838.

This symbolic meaning was fascinating not only for people then but also for those taking and looking at photographs now. And this fascinating game has a technical ease that can comfortably draw you in. From now on, humans no longer need artistic skills or craftsmen’s labor to freeze time. As long as the material and technical means allow, almost anyone can be a copier of a moment.

As can be expected, this great time evolved into a hysteria of capturing a moment on a social level. Like someone who has emerged from famine, the urge to capture a passing car, an ordinary sunset, the smile of an old coal miner, a spouse, and children began to manifest. With a drive similar to that of paintings and sculptures in ancient times. But with a significant difference: the enjoyment of this idolization and magic had been taken from a certain class and offered to a relatively wider audience.

Although all this may seem like the subjects of the high-resolution photographs exhibited by artists in modern galleries today, they were actually the general themes of the first images taken by people with cameras in their hands. You can take a look at the online archives of magazines like LIFE, which collected millions of photographs throughout history.

The Twin of Moments: Photographs that Freeze Special Moments

Although the creation of the twin of the moment spread widely with the invention of photography, it wasn’t until companies like Kodak produced portable, affordable, and easy-to-use cameras and films for mass sale that it was generally embraced by the public. However, starting in the mid-20th century, with the popularization of individual cameras, photography began to express a more balanced meaning at the social level. Thus, the “relative hunger” for photography—our instinct (panic) to capture every moment as if it were slipping away from our hands—reached a balance. Photography, like other methods, returned to its social function of creating meaning through sharing and connecting.

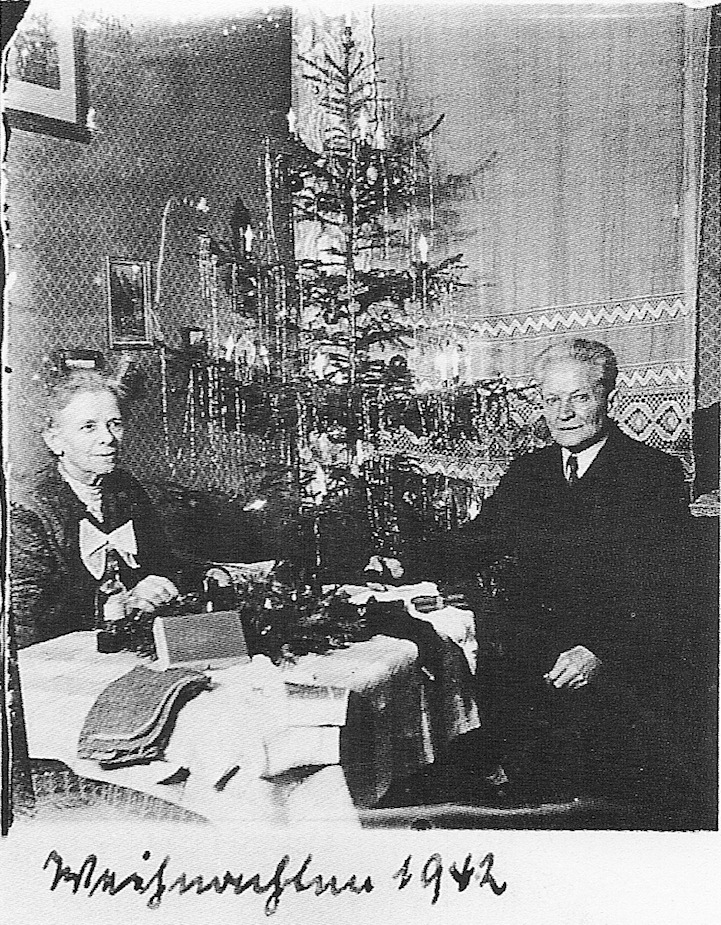

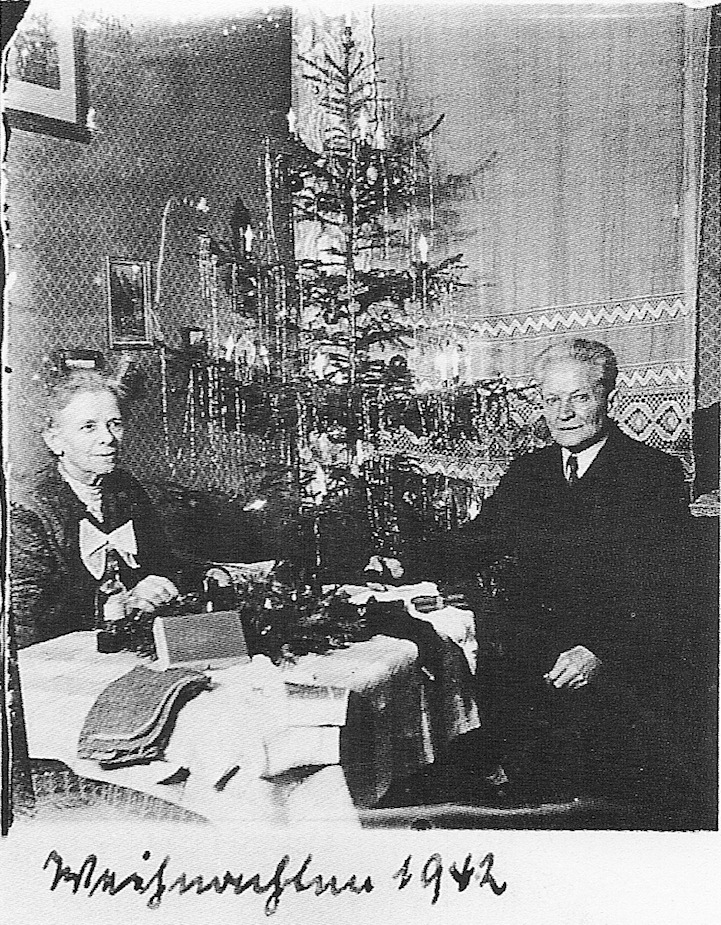

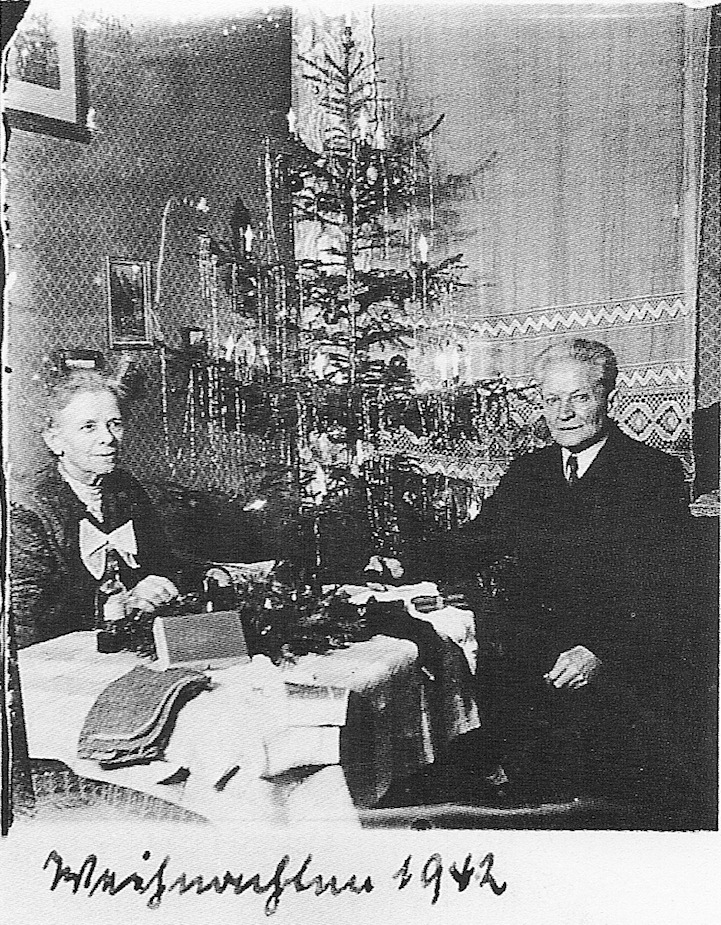

Take the couple Richard and Anna Wagner, for example. Starting in 1900, for 42 years, they took family photographs every New Year’s and sent them to their loved ones as cards. The twin moments in which people encapsulated their present lives and shared these moments with ‘desired’ individuals became significant. In a way, photography preserved its sociological place.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

For a beautiful analysis of the symbolic transformation of photography and the works of famous photographers, you can read Susan Sontag’s book On Photography.

Certainly, museums and private galleries continue to exhibit the works of photographers who capture the “interesting moments of life,” just as a medieval painter would present their paintings as artworks to kings. The sharing of “twin moments” from wars, historical events, and organizations became possible with commercial photographers. However, at the family and individual level, photography continued to live on by forming an organic connection with private life.

On an individual level, photography was used to strengthen and nurture our relationships with social groups. The extent to which individuals shared moments and memories with these groups and their cultures led them to enter a social whole. We can see traces of this quite clearly until just a few years ago: We showed photographs of the mystical places we visited, the unforgettable play of our childhood, the first tooth of our sibling, or the mischievous smile of our beloved to those we wanted to connect with. Thus, photography became a tangible supporter of verbal communication with others (and sometimes even with ourselves).

In other words, photographs had a Bourdieusian social function: preserving and recreating “beautiful” frames belonging to families and individual memories forever.

The Twin of Identity: Digital Photographs

The digital world of today and the perception of “culture” have undergone a massive transformation compared to a few decades ago. The relatively traditional and small-group life of humans has been reshaped by globalization and modern mass consumption/production tools. Technology has differentiated the connections between people.

Let’s consider the couple Richard and Anna Wagner again. A few decades ago, it was evident that they incurred serious financial costs, both materially and spiritually, while sharing the photographs they took during the World Wars period in Europe with their loved ones. However, if these elderly people were still alive, it would be a mystery whether they would send this year’s New Year’s photographs by mail or post them to a WhatsApp group. Thus, thinking about this function of photography in the present time may seem somewhat nostalgic.

In this new century, where the construction of identity outside of individuality and family has become pronounced, photography began to differentiate itself from merely being a medium for creating and sharing the twins of significant moments, becoming a method of self-presentation instead. Now, our concern is not to preserve our memories forever but to share our memories with others right at that moment, while experiencing that moment.

Consequently, just as the social hysteria of creating “twin moments” that arose with the invention of the camera transformed into a new hysteria of creating “twin identities” in a panic with the photographic cameras of portable phones and digital sharing platforms. We take photographs constantly, freezing moments continuously, and want to share, receive feedback, and read comments. The photograph taken and shared instantly with digital tools has transformed into a means of creating the moment itself rather than facilitating the revival of memories.

Previously, humans tried to capture extraordinary moments within the flow of life; now, they have begun to create moments to share, even living to share. We found ourselves thinking about the passport photo we would take before heading to the airport. After ordering food, we began to say, “Let’s take a picture when it arrives.” We started taking pictures of the cover before we even began reading a book. We began to take selfies in front of places we would never again remember, wanting to materialize the memory.

Digital Idols: Social Networks and Hashtags

In the last two decades, the social networks we’ve developed have gradually transformed into digital images filled with the history of our life and identity. In this new format, photographs have gradually lost their physical forms, and their meanings have transitioned to the public realm. The private aspects of photography—the cherished family photographs, the happiness reflected in a moment captured for a loved one—began to lose their significance. The meaning of photographs shifted towards public perception. The more likes and shares a photograph received, the more valid and ‘real’ that moment became.

Thus, photography found itself as an idol of the present, where it no longer depended solely on its existence but on the social functions it created. In other words, photographs transformed from the capture of a moment to the competition of an audience to perceive that moment. Thus, social media, the realm of the digital idol, became more significant than the moment itself. The ‘audience’ became the new counterpart of the ‘subject.’

Today, we follow various hashtags on social media platforms to reach as many likes as possible, to immortalize our memories within a life that seems increasingly fragile and ephemeral. The fragility of life was replaced by the fragility of digital footprints, the layers of which were rapidly disappearing in the flow of time.

Consequently, the symbolic meaning of the photograph of the couple Richard and Anna Wagner has transformed from preserving a memory for loved ones to creating a public presence that can be evaluated and critiqued by the larger social fabric.

The symbolic function of photography has changed; it has evolved from being an ordinary documentation of reality to a medium through which we construct and present our identities.

Conclusion

In essence, photographs, whether they are family treasures or works of art, have long held a significant place in human history as reflections of our existence and the journey of our lives. As technology and society have changed, so too has the role of photographs, shifting from intimate records of personal moments to a more complex interplay of identity, social interaction, and public perception in our digital age.

The hunger to capture, the pressure to share, and the pursuit of validation through the lens of a camera represent the evolution of our relationship with time and memory in a world that is constantly changing. We are left with the question: how do we navigate the balance between preserving our true selves and the curated identities we present to the world?

Moreover, we are no longer in a living room where we can hold our photo album and show it to our friends. Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and Pinterest have long filled the rooms of our lives.

The 15-Minute Interlude Between Being and Non-Being

Referring to Bourdieu’s definition from years ago, influenced by the intellectual movements of the mid-20th century, his interpretation of what constitutes a photograph was as follows:

“There’s no point in photographing something someone sees every day” (1990, p. 34).

Thus, according to him, not every picture taken could be counted as a photograph. Bourdieu delineated the two broad boundaries between photography as the concretization of personal moments and photography as an aesthetic art form. In today’s abundance of photographs and moments, it is evident that the boundaries of digital photographs must be redefined. The digital world has reshaped our connection with photography, not through the act of capturing images, but through moments, sharing, and communication. Consequently, photography has experienced erosion of its original meanings. Certainly, the hysterical sharing era we find ourselves in will, much like the early periods of analog photography, find its own balance.

But what is crucial here is how we position ourselves within this chaos.

If we believe every moment of our lives is special and that every ordinary moment (like our dinner, our car’s pause in morning traffic, the coffee we drink, or the book we read) is worth sharing with people we know and don’t know, we might be considered narcissistic and increasingly lonely, according to some studies.

If our sharing exceeds its social function of connecting with our families or loved ones, we might have entered an identity search in the parasocial loop, defining ourselves in relation to ‘famous’ or ‘idol’ figures.

Thus, we become quite susceptible to unhappiness and manipulation, embodying the characteristics of the ideal consumer.

With billion-dollar corporate valuations, and amidst serious data analyses, social experiments, and manipulative shares in these new living rooms, it wouldn’t hurt to critically reflect on ourselves and what we share before comfortably sinking into our chairs and creating our photo albums. Perhaps it’s reasonable to start with the question of whether we need a new identity that compels us towards this ‘ideal’ or to explore the new layers of our identities.

After all, the time between “I share, therefore I am” and “I am disappearing as I share” could be Warhol’s famous 15 minutes.

References and Recommendations

- Barthes, R. (1981), Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill and Wang.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990), Photography: A Middlebrow Art (trans. Shaun Whiteside), Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Edwards, E. (2005), ‘Photographs and the sound of history’, Visual Anthropology Review, 21: 1–2, pp. 27–46.

- Hjorth, L. (2009), ‘Photo shopping: A snapshot on camera phone practices in an age of Web 2.0’.

- Petersen, S. M. (2009), ‘Common banality: The affective character of photo sharing, everyday life and produsage cultures’, unpublished Ph.D., IT University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Van Dijk, J. (2008), ‘Digital photography: Communication, identity, memory’, Visual Communication, 7: 1, pp. 57–76.

- Simons, J. A. A. (2010), ‘Weightless photography’, in Johan Swinnen and Luc Deneulin (eds), The Weight of Photography: Photography History Theory and Criticism. Introductory Readings, Brussel: ASP Press, pp. 557–77.

- Sontag, S. (1973), On Photography, New York: Delta.

- Rubenstiein, D. and Sluis, K. (2008), ‘A life more photographic: Mapping the networked image’, Photographies, 1: 1, pp. 9–28.

- Murray, S. (2008), ‘Digital images, photo-sharing, and our shifting notions of everyday aesthetics’, Journal of Visual Culture, 7: 147, pp. 147–63.

(EN) (TR) (ES)

Paylaşıyorum, öyleyse varım

Zamanın modern putları: Fotoğraflar

Kodak, reklamlarında ‘anılarınızı sonsuza kadar saklıyoruz‘ dediğinde, ne hayatımız ne de anılarımız bu denli dijitalleşmişti henüz.

Ama sözlerini tuttular, bir kaç neslin anıları kağıtlar üzerine kazıdılar. Bazıları kırmızı odalarda binbir emekle üretildi, bazısı ise dükkanlarda 36lık, 24lük gruplar olarak. Beğendiklerimizi albümlerde sakladık, beğenmediklerimizi yığın halindeki fotoğraflar içine koyduk, üretim hatalarını da attık. Eledik bir nevi anıları. Hatta yeri geldi sıralardık önem ve zamana göre, albümlere yerleştirdik, küçük notlar yazdık arkalarına.

Geçmişteki bir anı somutlaştırıp tıpkı bir nesne gibi yanımızda taşıyabilme büyüsü idi onları kıymetli yapan. Modern birer put gibiydi fotoğraf. Zamanın sürükleyen, eskiten, yok eden korkutucu gücüne karşı aldığımız bir önlemdi. Dahası her put gibi, çok temel bir işlevi vardı:

Paylaşmak ve kaynaştırmak.

Buradaydım Elleri

Fotoğraf bu tip putların görece yenilerinden. Keza insanın zamandan korkusu ve anı kaçırma endişesi var oluşuyla birlikte gelen bir şey. Şu aşağıdaki ‘ben de varım, ben de buradayım’ ellerini düşünün. Bir nevi modern selfie gibi. Bundan binlerce yıl evvel yaşayan atalarımızın gülümseyen yüzlerini göremiyor, ellerini duvara dokundurdukları zaman hissettiklerini bilemiyor olabiliriz, ama ellerinin izlerini duvarlara geçirtmeye iten güdüyü yani zamanın enselerindeki baskısını, var olma hissini, o anı tabiri caizse ölümsüzleştirmek, paylaşmak ve birliktelik isteğini az çok tahmin edebiliyoruz.

İnsan zamanla duvara toz boya üfleyip elinin izini duvara yansıtmaktan daha komplike yöntemler geliştirdi. Eski çağlarda atalarımızın duvarlara görece ilkel yöntemlerle çizdiği resimler, avlar, festivaller yüzyıllar boyunca evrimleşti, resim, heykel ve mimari vesilesiyle kendine daha geniş bir ifade alanı buldu.

Gündelik hayat ve zaman ile kurulan bağ değiştikçe, bir tanrı, bir savaş anı , aristokrat bir ailenin öğleden sonrası, bir kralın portresi, hatta bir çiçek, bir gün batımı, sıradan bir mahalle pazarı somutlaşmaya başladı. Zamanın o belirsizliği içinde, tutuldu cımbızla, çekildi ve somutluğun içine bırakıldı. Bazısı sanatsal kaygılarla, bazısı toplumsal, bazısı ise bireysel yarattığımız bir dil olarak.

İlk fotoğraf : Güvencin yuvası

Yaşamın bir ikizini ima eden ve insanın kendi eliyle yaratmadığı nesneleri,yani fotoğraf (ve film),üretebilecek yollar bulmak, yüzyıllar boyunca mucit ve bilim adamlarının en büyük arzularından biri oldu. Nihayet 19 yy’a gelindiğinde, fotoğrafla ilgili başarılı teknikler geliştirildi ve tarihte ilk defa insan anın tıpa tıp ikizini yaratmayı başardı. Zamanın o acımasızlığa karşı kazanılmış belki de ilk büyük zaferdi bu. Hayat, olduğu gibi dondurulmuş ya da kayda alınabilmişti.

Aşağıdaki fotoğraf mesela, bir kaç yüz yıl önce emekli albay Niepce’in Paris’te ılık bir yaz gününde çektiği, kayıtlara geçen ilk fotoğraflardan biridir.

Adı Güvercin yuvası.

Albayın bir binanın tepesine çıkıp, sıradan bir günün ve sokağın görüntüsünü, kendi gözlerindeki görüntüsünün, dondurdulduğu bir an. Öyle ki şimdi bile, bu fotoğraf ile birlikte Niepce’nin 1838 yılındaki öğleden sonrasına gidip, bir nevi onun gözünden kopyalanan ve zamandan bağını koparmış bir anı görebiliyoruz.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

Bu sembolik anlam, sadece şimdi değil o zamanlarda da fotoğrafı çeken ve ona bakan insanlar için hayli büyüleyici. Ve bu büyüleyici bir oyun, seni de içine rahatlıkla çekebilecek teknik bir kolaylığa sahip. Bundan böyle, insanın zamanı dondurmak için, artistik yeteneklere ya da zanaatkar emeğine ihtiyacı yok. Maddi ve teknik imkanları el verdiğince, hemen hemen her insanın bir an kopyalayıcısı olması mümkün.

Tahmin edilebileceği üzere, bu büyük zamanlatoplumsal anlamda bir an yakalama histerisine evrildi. Kıtlıktan çıkmış birinin, yemeğe duyduğu iştah gibi, insan yoldaki bir arabayı, sıradan bir gün batımını, yaşlı bir kömürcünün gülümseyişini, eşini ve çocuklarını çekmeye başladı. Eski zamanlardaki resimlere, heykellere benzer bir güdüyle. Ama büyük bir farkla: Artık bu putlaştırma ve büyünün tadını çıkarma zevki, belirli bir zümrenin elinden alınmış, nazaran daha geniş bir kitleye bahsedilti.

- Tüm bunlar günümüzde sanatçıların modern galerilerde sergilediği yüksek çözünürlüklü fotoğrafların konuları gibi gözükse de, insanların ellerinde kameralarla çektiği ilk resimlerin genel temalarıydı aslında.Tarih boyunca milyonlarca fotoğrafı toplayan LIFE gibi dergilerin online arşivine bir göz atabilirsiniz

Anların ikizi: Özel Anları Donduran Fotoğraflar

Her ne kadar anın ikizinin yaratılması, fotoğrafın icadı ile geniş bir kitleye yayılsada, Kodak gibi firmaların taşınabilir, ucuz ve kullanımı kolay makine ve filmleri üretip kitlesel satışına kadar, halk tarafından genel olarak benimsenemedi. Ancak 20yy’ın ortalarından itibaren yaygınlaşan bireysel makineler ile, fotoğraf toplumsal düzeyde dha dengeli bir anlam ifade etmeye başladı. Böylece insanların da fotoğrafa olan ‘görece açlığı’, yani her anı ellerinden kaçıyormuşcasına yakalama güdüsü (paniği), dengeye ulaştı. Fotoğraf, tıpkı diğer yöntemler gibi, kendi içindeki sosyal işlevine, yani paylaşarak kaynaşmaya, yani anlam üreten an yakalamalarına geri döndü.

Richard ve Anna Wagner çifti mesela. 1900 yılından başlayarak 42 yıl boyunca her yıl başında aile fotoğraflarını çektiler ve bunları sevdiklerine birer kart olarak gönderdiler. İnsanların şimdiki zamanlarını hapsettiği bu ikiz anların, kişi için özel anlar olması ve bu anların ‘istenen’ kişilerle paylaşılması söz konusu idi artık. Bir nevi, fotoğraf sosyolojik anlamdaki yerini korudu.

- Fotoğrafın sembolik dönüşümü ve ünlü fotoğraf sanatçılarının eserleri ile ilgili güzel bir analiz için Susan Sontag- Fotoğraf üzerine kitabını okuyabilirsiniz.

Elbette müzeler ve özel galeriler ‘hayatın ilginç anlarını‘ yakalan fotoğraf sanatçıların eserlerini, tıpkı bir orta çağ ressamının resimlerini bir sanat eseri olarak krallara sunması gibi, sergilemeye devam etti. Savaşların, tarihi anların ve ordsganizasyonların ‘ikiz anlarının’ kitle ile paylaşılması ticari fotoğrafçılarla mümkün oldu. Ancak aile ve birey düzeyinde fotoğraf, özel hayatla organik bir bağ kurarak yaşamaya devam etti.

Fotoğraf bireysel düzlemde, toplumsal gruplarla olan ilişkimizi kuvvetlendirmek ve beslemek için kullanıldı. İnsan bu gruplarla ve onların kültürleriyle paylaştığı anların ve anıların ölçüsünde sosyal bir bütünlük içine girdi. Bunun izlerini, çok değil, bir kaç sene evveline kadar gayet net görebiliriz: Gittiğimiz mistik yerleri, çocukluğumuzun unutulmaz piyesini, kardeşimizin ilk dişini ya da sevgilimizin o muzip gülümsemesini, bir bağ kurmak istediğimiz insanlara bu fotoğraflar vesilesiyle gösterdik. Böylece fotoğraf başkaları ile (hatta bazen kendimizle olan) sözlü iletişimin somut bir destekçisi olurdu.

Diğer bir deyişle, fotoğrafların Bourdiuevari bir sosyal işlevi vardı.

Ailelere ve kişinin bireysel anılarına ait ‘güzel’ karelerin sonsuza dek saklanıp, yeniden yaratılması.

Kimliğin ikizi: Dijital Fotoğraflar

Günümüzün dijital dünyası ve ‘kültür’ algılayışı, bir kaç on yıl öncesine kıyasla devasa bir değişime uğradı. İnsanın görece geleneksel ve küçük gruplardan oluşan hayatı, küreselleşme ve modern kitle tüketim/üretim araçları ile yeniden şekillendi. Teknoloji, insanlar arasındaki bağları farklılaştırdı.

Richard ve Anna Wagner çiftini düşenelim mesela. Bundan bir kaç on yıl önce, Dünya Savaşları dönemi Avrupasında çektikleri fotoğrafları sevdikleri dostlarla paylaşırken gerek maddi gerek manevi anlamda ciddi bir maliyet içine girdikleri aşikar. Halbuki bu ihtiyarlar, hala yaşıyor olsalardı, bu seneki yıl başı fotoğraflarını hala posta ile mi gönderecekleri yoksa WhatsApp’ın grubuna toplu mesaj ile mi atacakları muamma. Bu nedenle fotoğrafın bu fonksiyonunu şimdiki zamana uyarlayıp düşünmek biraz nostaljik kaçabilir.

Bireyselliğin ve aile dışındaki kimlik inşasının ayyuka çıktığı bu yeni yüzyılda, fotoğraf artık önemli anların ikizini yaratıp sevdiklerinle paylaşmakta aracı olmaktan farklılaşmaya başlayıp, daha ziyade kendini dışa sunum yöntemi haline geldi. Artık derdimiz anılarımızı sonsuza kadar saklamak değil, anılarımızı bizzat o an da, o anı yaşarken başkaları ile paylaşmak istiyoruz.

Haliyle tıpkı fotoğraf makinesinin icadıyla toplumsal olarak yaşanılan histerik ‘an ikizi’ yaratma akımı, günümüzdeki taşınabilir telefonların fotoğraf kameraları ve dijital paylaşım platformları ile yeni bir histeriyle, panik halinde ‘kimlik ikizi’ yaratma telaşına dönüştü. Durmadan fotoğraf çekiyor, durmadan an’ları donduruyor, sürekli paylaşmak, geri bildirim almak, yorumlar okumak istiyoruz. Elimizdeki dijital araçlarla anında çekilip paylaşılan fotoğraf, anıların canlanmasına vesile olmaktansa, şimdiki zamanda bizzat anı yaratan bir araca dönüştü bile.

Önceden hayatın akışı içindeki sıradışı anları yakalamaya çabalayan insan, şimdi paylaşmak için an yaratmaya başladı, hatta bir nevi paylaşmak için yaşamaya başladı. Havalimanına gitmeden orada çekeceğimiz pasaport fotoğrafını düşünür olduk. Yemeği sipariş ettikten sonra, gelse de çeksek demeye başladık. Daha kitabı okumaya başlamadan kapağını, kahveyi içmeden dumanını çeker olduk. Bir yeri gezerken daha ‘iyi bir kimlik’ yaratacak anlar yaratıp ve bunlarıu paylaşacak yerlere gider olduk. Dijital fotoğraf zamanla olan yarışını belli ki kazandı, hatta öyle ki onu solladı.

Artık an yaşanmadan fotoğrafını çekiyor, anı sonsuzlaştırmak için değil, ‘yeni kimliğimizi’ ispat için kareler yakalıyoruz. Bir nevi, “yaşadığımız kimliğin ikizi olan” nostaljik fotoğrafın yerini, “paylaşmak için yarattığımız anların ve kimliklerin” vesilesi olan dijital fotoğraflar aldı.

Dahası, artık fotoğraf albümümüzü kucağımıza koyup arkadaşlarımıza göstereceğimiz bir oturma odasında değiliz. Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest gibi platformlar hayatımızın odalarını çoktan doldurdular.

Var ile yok arası 15 dakika

Bourdiue’nun yıllar evvel, 20 yy ortasındaki entellektüel hareketin etkisindeki tanımından hareketle, neyin fotoğraf olup olmayacağına dair yorumu şöyleydi:

‘birinin her gün gördüğü bir şeyin fotoğrafını çekmenin anlamı yok’ (1990, s34)

Haliyle O’na göre çekilen her resim, bir fotoğraf olarak sayılamazdı. Bourdiue, kişi için özel anların somutlaşması olarak fotoğraf ile estetik bir sanat dalı olarak fotoğrafın iki geniş sınırını çiziyordu. Günümüzdeki bu fotoğraf ve an bolluğu içinde, dijital fotoğrafların sınırlarının yeninden tanımlanması gerektiği aşikar. Keza dijital dünya, fotoğraf ile değil, an, paylaşım ve iletişim ile olan bağımızı yeniden tanımladı. Haliyle fotoğraf eski anlamlarında aşınmalar yaşadı. Muhakak ki içinde bulunduğumuz histerik paylaşım dönemi, tıpkı analog fotoğrafın ilk dönemlerinde olduğu gibi, kendi dengesini bulacak.

Ama burada muhim olan, kendimizi bu kaos içinde nasıl konumlandıracağımız?

Eğer hayatımızın her anının özel olduğunu düşünüyor ve sıradan her anımızı tanıdığımız ve tanımadığımız insanlarla paylaşmaya değer olduğunu (akşam yemeğimiz, sabah trafiğinde araba içindeki duruşumuz, içtiğimiz bir kahve ya da okuduğumuz bir kitap gibi), bazı araştırmalara göre narsist ve olabildiğince yalnız olabiliriz.

Eğer paylaşımlarımız ailelerimiz ya da yakınlarımızla kaynaşmakla ilgili sosyal işlevini aştıysa, parasosyal döngüdeki bir kimlik arayışına girmiş, kendimizi ‘ünlü’ ya da ‘idol’ kişiler üzerinde tanımlamış olabiliriz.

Haliyle mutsuzluğa ve manipulasyona oldukça açık bir halde, ideal bir tüketici kıvamından da bahsetmek mümkün.

Milyar dolarlık şirket değerleri ile, üzerinde ciddi data analizlerinin, sosyal deneylerin, manipulatif paylaşımların olduğu bu yeni oturma odalarımızda, sırtımızı rahatça koltuğa yaslayıp, fotoğraf albümlerimizi yaratmadan evvel, kendimize ve paylaştıklarımıza sorgular gözle bakmaktan zarar gelmez. Belki de ait olmadığımız ve bizi bu ‘ideale’ zorlayan yeni bir kimliğe mi, yoksa kimliğimizdeki yeni katmanları keşfetmeye mi ihtiyacımız olduğu sorusu ile başlamak epey makul.

Neticede paylaşıyorum öyleyse varım ile paylaştıkça yok oluyorum arasındaki süre, Warhol’un meşhur 15 dakikası olabilir.

Kaynakça ve Öneriler

Barthes, R. (1981), Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill and Wang.

Bourdieu, P. (1990), Photography: A Middlebrow Art (trans. Shaun Whiteside), Cambridge: Polity Press.

Edwards, E. (2005), ‘Photographs and the sound of history’, Visual Anthropology Review, 21: 1–2,pp. 27–46.

Hjorth, L. (2009), ‘Photo shopping: A snapshot on camera phone practices in an age of Web 2.0’,

Petersen, S. M. (2009), ‘Common banality: The affective character of photo sharing, everyday life and produsage cultures’, unpublished Ph.D., IT University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Van Dijk, J. (2008), ‘Digital photography: Communication, identity, memory’, Visual Communication,

7: 1, pp. 57–76.

Simons, J. A. A. (2010), ‘Weightless photography’, in Johan Swinnen and Luc Deneulin (eds), The Weight of Photography: Photography History Theory and Criticism. Introductory Readings, Brussel: ASP Press, pp. 557–77.

Sontag, S. (1973), On Photography, New York: Delta.

Rubenstiein, D. and Sluis, K. (2008), ‘A life more photographic: Mapping the networked image’,Photographies, 1: 1, pp. 9–28.

Murray, S. (2008), ‘Digital images, photo-sharing, and our shifting notions of everyday aesthetics’,Journal of Visual Culture, 7: 147, pp. 147–63. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 22: 3, pp. 157–59.

(EN) (TR) (ES)

Comparto, por lo tanto existo

Los ídolos modernos del tiempo: Fotografías

Cuando Kodak dijo en sus anuncios “guardamos tus recuerdos para siempre”, ni nuestras vidas ni nuestros recuerdos estaban tan digitalizados.

Pero cumplieron su promesa, grabaron los recuerdos de varias generaciones en papeles. Algunos fueron producidos con esfuerzo en habitaciones rojas, otros se compraron en tiendas en grupos de 36 o 24. Conservamos los que nos gustaron en álbumes, y los que no, los pusimos en montones de fotos, desechando los errores de producción. De alguna manera, eliminamos recuerdos. A veces incluso los ordenamos por importancia y tiempo, los colocamos en álbumes y escribimos pequeñas notas en la parte de atrás.

La magia que los hacía valiosos era la capacidad de materializar un recuerdo del pasado y llevarlo con nosotros como un objeto. La fotografía era como un ídolo moderno. Era una medida de protección contra el aterrador poder del tiempo, que arrastra, envejece y destruye. Además, como todo ídolo, tenía una función muy básica:

Compartir y conectar.

Aquí estuve con las manos

La fotografía es uno de los ídolos relativamente nuevos. La angustia del ser humano por el tiempo y el miedo a perder recuerdos es algo que viene con su existencia. Piensa en las manos de “yo también estoy aquí, yo también estoy presente” abajo. Algo así como un selfie moderno. No podemos ver los rostros sonrientes de nuestros ancestros que vivieron hace miles de años, ni sabemos lo que sintieron al tocar la pared, pero podemos inferir el impulso que los llevó a dejar las huellas de sus manos en las paredes, es decir, la presión del tiempo en sus cuellos, la sensación de existencia, el deseo de inmortalizar el momento y compartirlo, y el anhelo de conexión.

Primera fotografía: El nido de palomas

Buscar formas de producir un duplicado de la vida, es decir, de crear objetos que el ser humano no ha creado con su propia mano, como la fotografía (y el cine), fue uno de los mayores deseos de inventores y científicos durante siglos. Finalmente, en el siglo XIX, se desarrollaron técnicas exitosas relacionadas con la fotografía y por primera vez en la historia, el ser humano logró crear un duplicado exacto del momento. Esta fue quizás la primera gran victoria contra la brutalidad del tiempo. La vida había sido congelada o registrada tal como era.

La fotografía a continuación, por ejemplo, es una de las primeras fotografías registradas, tomada por el coronel Niepce en un cálido día de verano en París hace algunos cientos de años.

Se llama “El nido de palomas”.

El coronel subió a la azotea de un edificio y capturó la imagen de un día y una calle ordinaria, un momento congelado de lo que vio con sus propios ojos. De tal manera que incluso ahora, con esta fotografía, podemos regresar a la tarde de Niepce en 1838 y ver un recuerdo que ha perdido su conexión con el tiempo.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

Louis Jacques Mande DAGUERRE,Boulevard du Tample,Paris, 1838.

Este significado simbólico era fascinante no solo para quienes tomaban la fotografía en ese momento, sino también para aquellos que la miraban. Y este juego fascinante tenía una facilidad técnica que podía absorberte fácilmente. A partir de ahora, la humanidad no necesitaba habilidades artísticas o el esfuerzo de un artesano para congelar el tiempo. Siempre que las posibilidades materiales y técnicas lo permitieran, prácticamente cualquier persona podía ser un replicador de momentos.

Como se puede suponer, esta gran captura de momentos se convirtió en una histeria social. Al igual que alguien que ha salido de una hambruna y anhela comida, la gente comenzó a capturar un coche en la carretera, un atardecer ordinario, la sonrisa de un viejo carbonero, su pareja y sus hijos. Con un impulso similar al de las imágenes de tiempos antiguos. Pero con una gran diferencia: el placer de esta idolatría y magia ya no estaba reservado a un grupo selecto, se extendió a una audiencia más amplia.

Todo esto puede parecerse a los temas de las fotografías de alta resolución que los artistas exhiben en galerías modernas hoy en día, pero en realidad eran los temas generales de las primeras imágenes tomadas por personas con cámaras. Puedes echar un vistazo al archivo en línea de revistas como LIFE, que ha recopilado millones de fotografías a lo largo de la historia.

Los gemelos del momento: Fotografías que congelan momentos especiales

Aunque la creación de un gemelo del momento se difundió con la invención de la fotografía, no fue hasta que empresas como Kodak produjeron cámaras y películas portátiles, económicas y fáciles de usar y las vendieron de manera masiva, que fue adoptada por el público en general. Sin embargo, a partir de la mitad del siglo XX, con la proliferación de cámaras individuales, la fotografía comenzó a tener un significado social más equilibrado. Así, el “apetito relativo” de la gente por la fotografía, es decir, el impulso (pánico) de capturar cada momento como si se les escapara de las manos, alcanzó un equilibrio. La fotografía, al igual que otros métodos, regresó a su función social, es decir, a la conexión y el intercambio, es decir, a las capturas de momentos que producen significado.

Por ejemplo, la pareja Richard y Anna Wagner. Desde 1900, durante 42 años, tomaron fotos familiares cada Año Nuevo y las enviaron a sus seres queridos como tarjetas. Estos gemelos del momento, que la gente atrapaba en el tiempo presente, se convirtieron en momentos especiales para el individuo y ya se trataba de compartir esos momentos con las “personas deseadas”. En cierto sentido, la fotografía mantuvo su lugar en un sentido sociológico.

Para más detalles: https://mymodernmet.com/richard-and-anna-wagner-christmas-portraits/

El gemelo de la identidad: Fotografías digitales

La percepción del mundo digital actual y de la “cultura” ha cambiado drásticamente en comparación con hace unas pocas décadas. La vida del ser humano, compuesta de grupos relativamente tradicionales y pequeños, ha sido reformada por la globalización y las herramientas modernas de consumo/producción masiva. La tecnología ha transformado las conexiones entre las personas.

Tomemos a Richard y Anna Wagner como ejemplo. Es evidente que hace unas pocas décadas, compartir las fotos que tomaron en la Europa de la Primera y Segunda Guerra Mundial implicaba costos significativos tanto materiales como espirituales. Sin embargo, si estos ancianos estuvieran vivos hoy, sería un misterio si enviarían las fotos de este Año Nuevo por correo o las enviarían en un mensaje grupal de WhatsApp. Por lo tanto, adaptar y pensar en esta función de la fotografía al tiempo presente puede parecer un poco nostálgico.

En este nuevo siglo, donde la construcción de la identidad individual y fuera del ámbito familiar ha cobrado fuerza, la fotografía ha comenzado a diferenciarse de ser un medio para crear gemelos de momentos importantes y compartirlos con seres queridos, convirtiéndose en un método para presentarse al mundo

El sentido de inmortalidad que perseguimos se ha convertido en un acto de inmortalidad digital. En las redes sociales, Instagram, por ejemplo, muchos construyen sus imágenes y recuerdos, que a menudo están lejos de la “realidad”, como una especie de arte. Ahora, al mirar estas fotos de amigos y personas cercanas, solo podemos percibir las diferentes imágenes de ellos: felicidad, alegría, satisfacción, cultura, etc., y a veces todo esto se vuelve tan comercial y absorbente que los momentos se ven vacíos de significado. Pero, al mismo tiempo, esta captura de momentos ha permitido que otros conecten con nosotros y nuestras historias, incluso en la distancia. Entonces, al final del día, podemos ver que esta captura de imágenes ha tomado una nueva forma, donde el significado puede ser más abstracto y vacío.

El significado y el significado de la fotografía han ido evolucionando. Si antes se pensaba que la fotografía era un medio para recordar el pasado, ahora se ha convertido en un medio para construir el futuro, es decir, en un medio para imaginar y proyectar nuestro futuro. El esfuerzo del ser humano por congelar el tiempo ha encontrado una nueva forma de reproducirse. La fotografía ha dejado de ser un medio para compartir momentos y ahora, en un sentido más amplio, es un medio para construir un sentido del tiempo. Los seres humanos no solo buscan inmortalizarse, sino que buscan construir un futuro en este juego moderno de imágenes.

El ídolo moderno: Una nueva mirada a la fotografía

A lo largo de la historia, las imágenes han servido para conectarnos con otros y con nuestra memoria. Sin embargo, al mirar la historia de la fotografía, podemos ver que este impulso humano ha ido más allá de su necesidad inicial. La tecnología ha desarrollado esta capacidad humana de capturar momentos en un contexto social, lo que permite a muchas personas, a veces incluso en contraposición a sus deseos, vivir y crear nuevas culturas. La fotografía no solo crea un vínculo con los recuerdos, sino que también desarrolla nuevos vínculos entre las personas y su entorno. Un “Yo” vacío de significado frente a la realidad, donde nos volvemos visibles, como un ídolo moderno, a través de las imágenes que producimos. En este sentido, la búsqueda de la inmortalidad ha evolucionado hacia una búsqueda de conexión con los demás. Esta búsqueda nos lleva a ver y experimentar una realidad cambiante, donde la relación entre nosotros y la vida misma se convierte en un tema en constante evolución.

Entre ser y no ser hay 15 minutos. Basándose en la definición de Bourdieu, influenciada por el movimiento intelectual de mediados del siglo XX, su interpretación sobre lo que puede ser o no una fotografía era la siguiente:

“No tiene sentido tomar una foto de algo que alguien ve todos los días” (1990, p. 34).

Por lo tanto, según él, no todas las imágenes tomadas podían considerarse fotografías. Bourdieu delineaba los dos amplios límites de la fotografía como una concreción de momentos especiales para la persona y como una forma de arte estético. Es evidente que, en la abundancia actual de fotografías y momentos, es necesario redefinir los límites de las fotografías digitales. De hecho, el mundo digital ha redefinido nuestra relación con la fotografía en términos de momento, compartir y comunicación. Así, la fotografía ha sufrido desgastes en sus significados anteriores. Sin duda, el periodo de histeria compartida en el que nos encontramos encontrará su propio equilibrio, tal como ocurrió en los primeros tiempos de la fotografía analógica.

Pero aquí lo importante es, ¿cómo nos posicionamos dentro de este caos?

Si pensamos que cada momento de nuestras vidas es especial y que cada instante ordinario merece ser compartido con personas conocidas o desconocidas (como nuestra cena, nuestra postura en el tráfico matutino, un café que tomamos o un libro que leemos), podríamos ser considerados, según algunas investigaciones, narcisistas y extremadamente solitarios.

Si nuestras publicaciones han superado su función social de conectar con nuestras familias o seres cercanos, podríamos haber entrado en una búsqueda de identidad en un ciclo parasocial, definiéndonos a través de personas “famosas” o “íconos”.

Así, se podría hablar de un estado de consumidor ideal que está bastante abierto a la infelicidad y a la manipulación.

Con valores de empresas multimillonarias y serios análisis de datos, experimentos sociales y comparticiones manipulativas en nuestras nuevas salas de estar, no estaría de más mirarnos a nosotros mismos y a lo que compartimos con un ojo crítico antes de relajarnos cómodamente en nuestro sillón y crear nuestros álbumes fotográficos. Tal vez sea razonable comenzar con la pregunta de si necesitamos una nueva identidad que nos empuje a este “ideal” al que no pertenecemos, o si debemos descubrir nuevas capas dentro de nuestra identidad.

Al final, el tiempo entre “comparto, luego existo” y “me estoy desvaneciendo a medida que comparto” podría ser los famosos 15 minutos de Warhol.

Además, ya no estamos en una sala de estar donde podemos sostener nuestro álbum de fotos y mostrarlo a nuestros amigos. Plataformas como Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr y Pinterest han llenado las habitaciones de nuestras vidas desde hace tiempo.

El Interludio de 15 Minutos Entre el Ser y el No-Ser

Para un hermoso análisis sobre la transformación simbólica de la fotografía y las obras de fotógrafos famosos, puedes leer el libro “Sobre la fotografía” de Susan Sontag.

Por supuesto, los museos y galerías privadas continúan exhibiendo las obras de fotógrafos que han capturado “momentos interesantes de la vida”, al igual que un pintor medieval presentaba sus obras como arte a los reyes. Compartir los “gemelos” de las guerras, momentos históricos y organizaciones con las masas fue posible gracias a fotógrafos comerciales. Sin embargo, a nivel familiar e individual, la fotografía continuó viviendo con un vínculo orgánico con la vida privada.

La fotografía, en el plano individual, se utilizó para fortalecer y nutrir nuestra relación con grupos sociales. Las personas entraron en una totalidad social medida por los momentos y recuerdos que compartieron con estos grupos y sus culturas. Podemos ver las huellas de esto claramente hasta hace unos años: mostramos a las personas con las que queríamos conectarnos estas fotos de lugares místicos que visitamos, la obra inolvidable de nuestra infancia, el primer diente de nuestro hermano o la traviesa sonrisa de nuestra pareja. Así, la fotografía se convirtió en un apoyo tangible para la comunicación verbal con los demás (y a veces incluso con nosotros mismos).

En otras palabras, las fotografías tenían una función social de tipo bourdieusiano.

Conservar y recrear para siempre los “hermosos” cuadros de los recuerdos de las familias y los individuos.

Referencias y Sugerencias

Barthes, R. (1981), Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Nueva York: Hill and Wang.

Bourdieu, P. (1990), Photography: A Middlebrow Art (trad. Shaun Whiteside), Cambridge: Polity Press.

Edwards, E. (2005), “Photographs and the sound of history”, Visual Anthropology Review, 21: 1–2, pp. 27–46.

Hjorth, L. (2009), “Photo shopping: A snapshot on camera phone practices in an age of Web 2.0”.

Petersen, S. M. (2009), “Common banality: The affective character of photo sharing, everyday life and produsage cultures”, tesis doctoral no publicada, Universidad de IT de Copenhague, Copenhague, Dinamarca.

Van Dijk, J. (2008), “Digital photography: Communication, identity, memory”, Visual Communication, 7: 1, pp. 57–76.

Simons, J. A. A. (2010), “Weightless photography”, en Johan Swinnen y Luc Deneulin (eds), The Weight of Photography: Photography History Theory and Criticism. Introductory Readings, Bruselas: ASP Press, pp. 557–77.

Sontag, S. (1973), On Photography, Nueva York: Delta.

Rubenstein, D. y Sluis, K. (2008), “A life more photographic: Mapping the networked image”, Photographies, 1: 1, pp. 9–28.

Murray, S. (2008), “Digital images, photo-sharing, and our shifting notions of everyday aesthetics”, Journal of Visual Culture, 7: 147, pp. 147–63. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 22: 3, pp. 157–59.